It’s no surprise in this political year, when as Nikki Haley said as part of her now failed campaign stump speech “the world is on fire,” that arts organizations like the Oscars and SXSW, down in barbecue central Austin, would be platforms for protest and response. You had to turn on CNN, however, to learn anything was happening at SXSW, where I went to check out the films more than the tunes, and it was pretty much business as usual: some good docs, a lackluster group of fiction films that sound like Sundance rejects: “Bionico is a hopeless romantic addicted to crack who along with Calvita, his drug partner, tried to find a job, a house and a wedding ring to marry La Flaca, his fiancée.” Not sure whether both Bionico and Calvita are marrying La Flaca, the fiancée, but good for her if they are. And with all apologies to that film, which I didn’t see and shall remain nameless, a lot of the fiction lineup reads like that, all looking for a way out of distribution limbo: they got made, and now what?

The good news at South By, as it’s called by the thousands who show up for the two-week extravaganza in Texas’ capital city, is that just like Sundance there is a surfeit of interesting docs around, particularly music docs that got made during pandemic — because they’re economical to make, relying on archival footage and talking head witness testimonies. These docs open the doors of perception to careers of past stars you may pigeonholed on a playlist somewhere, but whose work has formed the background of our FM radio lives or our disk and tape laced childhoods. There is now something of a goldrush of families and friends who seem to have gotten films made very much either to revive their fallen hero’s legacy or in the case of the musicians, their catalog revenue streams, or both.

Bob Marley: One Love, which Paramount opened Valentine’s Day, has racked up a decent enough $90 million domestic boxoffice and $161 total worldwide to date. It didn’t go to Sundance or South By because Paramount calculated it didn’t need the festivals and didn’t want the risk of bad reviews, which the marketing department could simply roll over in commercial release. A middling biopic which emphasized Marley’s nonviolence, it had a great performance by Kingsley Ben Adir as Marley—he played Malcolm X in One Night in Miami four years ago, and a good one by Lashana Lynch, who played the MI6 agent in No Time to Die in 2021, here as Marley’s wife, Rita. Both Londoners of Caribbean ethnicity.

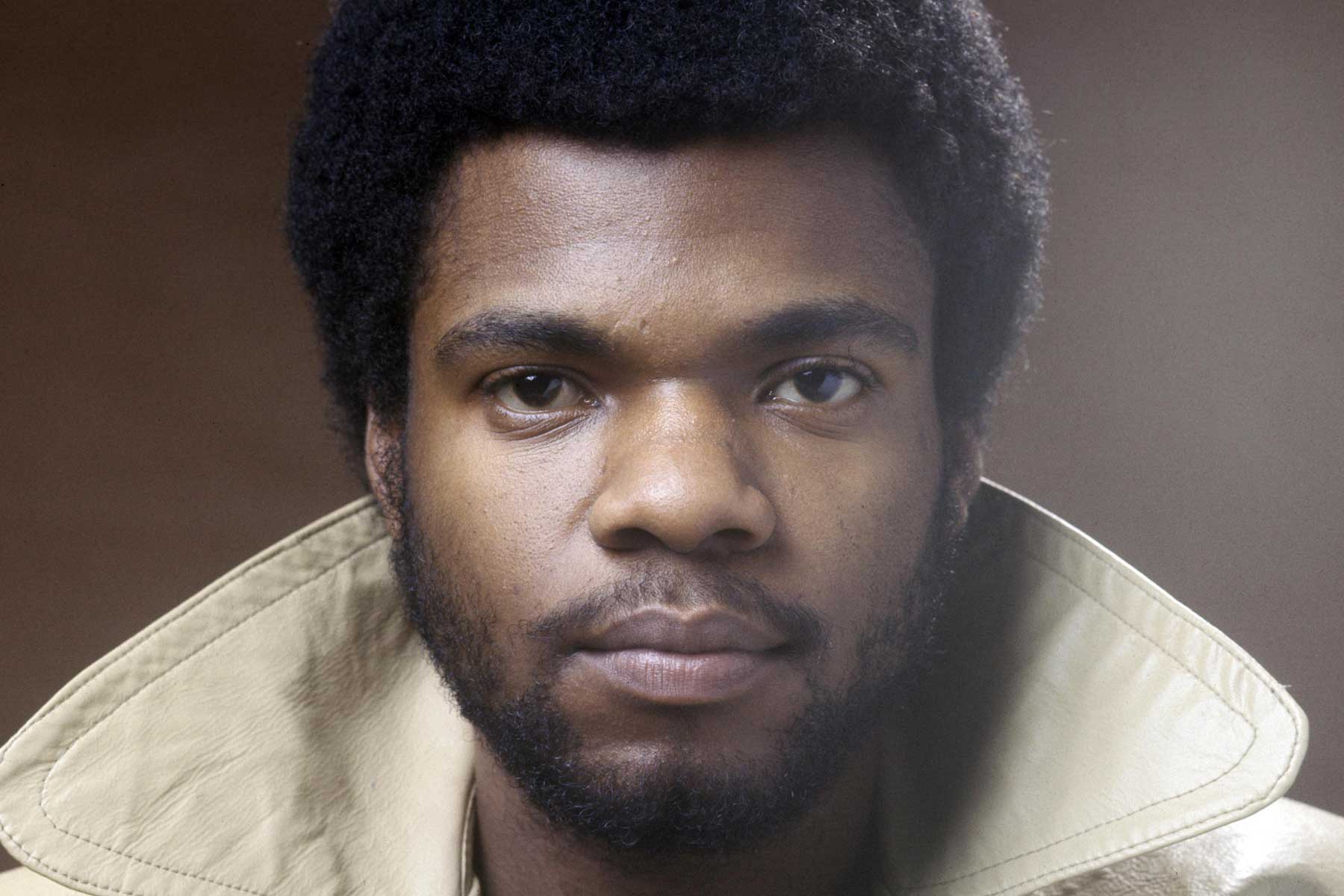

(By contrast) Billy Preston: That’s the Way God Planned it, a doc by Paris Barclay about the perennial rock and soul prodigy who was most comfortable in the shadows of great stars and made them look and sound greater, could just as easily have played Sundance as South By, It is in its overall arc similar to Dawn Porter’s doc Luther: Never Too Much, about Luther Vandross, and I could easily imagine a scenario where Sundance decided to take one and jumped the Vandross way, and South By to its credit nailed the Preston doc.

Both have as their organizing principal that these two gifted, gospel-schooled musicians, were intensely closeted and deeply fearful of coming out to the world and most particularly the church world that created them, though, as one witness says about 25 minutes into the Preston doc, “There were a lot of queens in the choir.”

It opens with the George Harrison led Concert for Bangladesh in New York in August 1971 that featured Ringo, Dylan, Eric Clapton, Leon Russell and Ravi Shankar (not in the film). And a magical moment when Preston got the gospel heebie-jeebies and jumped up from the piano to do a spirit driven dance that floored the stars and the fans. He was irrepressible, Barclay shows, starting with his Baptist church work in Louisiana as a kid, then worming his way into Ray Charles’ orbit, Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Norah Jones, Streisand, the Stones and the Beatles, who heard him in ’62 when they opened for Little Richard in Hamburg and relied on him until they blew up. Prestons’ career was up—he had a ranch in Topanga Canyon with horses—before it went down and sideways after that.

He wrote “You Are So Beautiful to Me” which Joe Cocker rode to glory, wrote and sang Nothin’ From Nothin’ on Saturday Night Live’s first show in October 1975, then hit the cocaine and drink skids, is sentenced to rehab after sexual assault charges are dismissed but gets three years in a California prison for cocaine in 1997, and while there is charged with arson and insurance fraud. Eric Clapton brought him back in 2002 after Harrison died for The Concert for George at the Royal Albert Hall, where Preston brings the house to tears with “Isn’t It A Pity.” He died broke at 59 in 2006, and you can’t help but dissolve into a puddle in your seat.

Alas and alack, Rocker Sam Moore filed suit against the Whitehorse Preston production team, claiming that the filmmakers enlisted his participation without disclosing their intention to make Preston’s homosexuality the spine of the story. I’m not sure where the suit stands now, but the film did have its world premiere at SXSW. Preston’s God-given talent, like Bradley Cooper’s fictionalized profile of Leonard Bernstein last year in Maestro, or all the docs and biopics to date of recent great artists, they all had a devil of a time with their fear of mid-20th century America’s expectations.

Preston’s story couples with Jamila Wignot’s doc about Stax Records, Stax: Soulsville USA. It’s a great Memphis story, not the Elvis story, but taken from Toronto music historian Rob Bowman’s 2003 book, Soulsville USA: The Story of Stax Records, beginning with the story of Jim Stewart, a failed white songwriter who wanted to start a Country & Western studio and label, and his sister, Estelle Axton, who ran the next-door Satellite Records shop, which turned out to be a neighborhood kid hangout. Taking the St from Stewart and the AX from Axton, and they got Stax. Which turned out to be something between a musicians recruitment center and a test market for which way the Memphis sound was blowing.

That it turned into a soul factory built by Carla and Rufus’ “Cause I Love You” and later Booker T and Otis Redding, is testimony not only to the white guys being open to the black neighborhood they were in, but to creating the model of black and white artists working inside the dream MLK had in the city where he was killed at the Lorraine Motel, the place where Stax artists used to hang. Of course, Stewart signed a terrible contract in 1965 that transferred all catalog rights to Atlantic Records in perpetuity, which is how Wignot leaves things at the end of episode two of a four-parter that drops later this year On Max, the strange down-market branding HBO gave itself under its new ownership.

Stax: Soulsville USA is worth waiting for, and I am Harlan Jacobson sitting by the dock of the bay, waiting for more.

By Harlan Jacobson