In HG Wells’ original 1897 novel, The Invisible Man, the central character, Griffin, is a medical student turned optical scientist who’s successfully unlocked the key to how we see—and turned himself invisible. Irreversibly. When he arrives at a country inn wrapped in bandages, wearing a country hat and a fake pink nose, and toting a complete laboratory setup to try to reverse-engineer his way back to visible, he is highly unpleasant by English country inn, family standards. Wells laid out the big questions of the day: science, the individual, class, the state, and the underlying cause of terror which had become a feature of political life in the revolutionary world articulated by Marx. Wells’ invisible man is in debt up to his ears, he’s angry, and he burns down the house in a crime wave. No one believes what they can’t see when it comes to science, but does believe it when it comes to religion. In short, Wells created science-fiction.

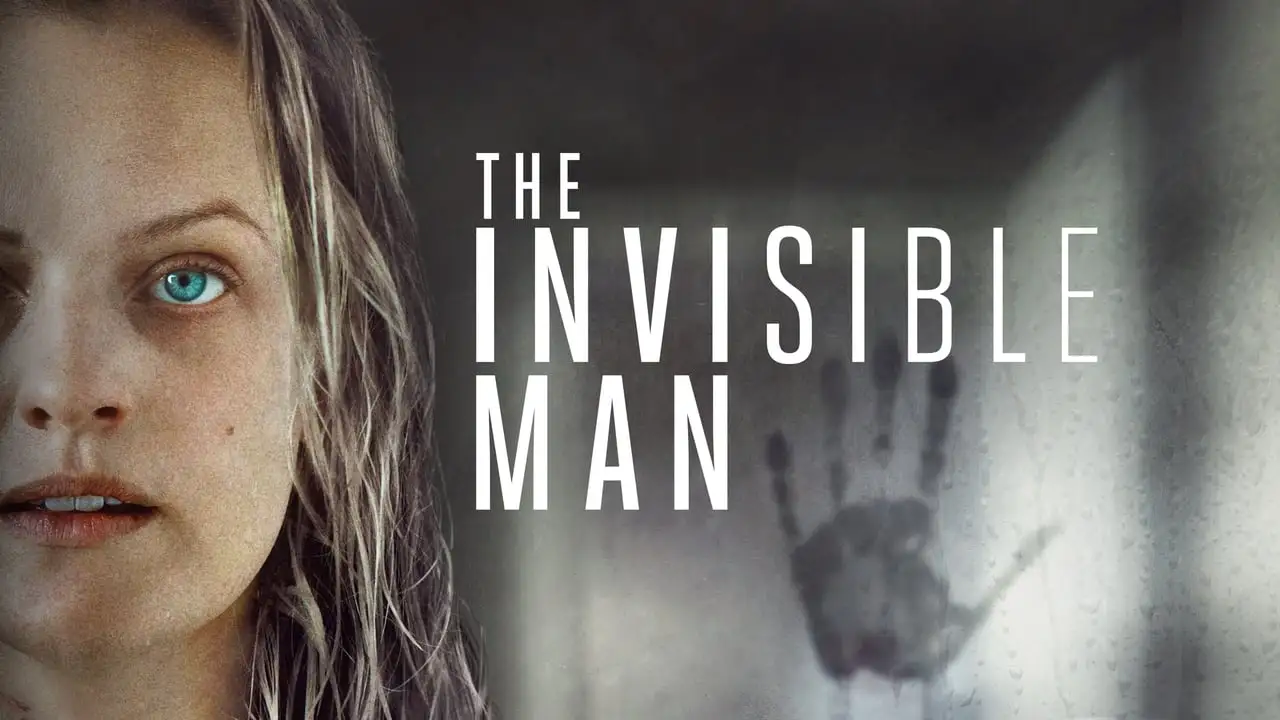

Writer-director Leigh Whannell’s The Invisible Man is only “inspired by” HG Wells’ original 1897 novel. And it’s not a remake of James Whale’s classic 1933 film starring a young Claude Rains as Dr. Jack Griffin, a murderous scientist. It’s not about the discontents of an invisible man at all, in fact. It is anything but.

Instead, Whannell’s adaptation means to be up to the minute: The central idea this Invisible Man is a woman’s story. Nobody hears or believes Elisabeth Moss as Cecilia Kass, when she reports being terrorized by her boyfriend. Why would they? He’s dead. He committed suicide after she escaped their high-tech mansion by the sea in San Francisco (though it was filmed mostly in studio interiors in tax-supported, low budget Australia). Played by Oliver Jackson-Cohen, Adrian Griffin, a nod to Wells’ Griffin, is a dot.com billionaire optical genius whom Elizabeth intuits has figured out how to make himself invisible, and is therefore very undead. Being invisible just allows his clingy, controlling self to get that much unbearably closer to every move she makes. Because they can’t see him, she must be crazy.

And thus we have the modern application of political metaphor cloaked inside the sci-fi genre: this Invisible Man is textbook Harvey Weinstein. He’s stalking me, terrorizing me, flinging me around the bed room in a sometimes horrible, sometimes slapstick sequence that no one sees or believes. Help!

It’s pretty clever to load the politics of #MeToo onto the mechanisms of a horror film. Everyone inside the movie and out is jumpy. The film is the work of Jordan Peele’s Blumhouse Productions, which financed Get out for Peele to direct and signed on Moss to appear in his follow-up film, Us, and to star here. To his credit, with Peele producing, Whannell is reasonably restrained in his direction of harum-scarum scenes, which could’ve detracted from simply psychologically terrorizing his female character. Only Cecilia and you, the audience, are in on the secret, as Cecilia stands in for getting under your skin. You believe her from the get-go, because you can. While the film is called The Invisible Man, the characters in her life just think Cecilia is crazy, Hitchcock crazy, an unreliable narrator. It is in essence the 21st Century story of being an invisible woman.

In the aftermath of her escape from the home surveillance stronghold that begins the film, Cecilia flees courtesy of an escape aided by her sister, who significantly will come to doubt her sanity. Cecilia puts in at the house of her best friend, James (Aldis Hodge of Clemency), and the news then carries the story of Griffin, her boyfriend’s, suicide. So Cecilia sinks in safely to bunk in with her god-daughter, Sydney (Storm Reid), James’ barely teenage daughter. All seems calm. Even good, as Griffin’s lawyer-brother calls to say his late brother’s estate left her $5 million in payable chunks, if she can keep her nose clean. Think she’ll be able to?

That’s when Cecilia is awakened by hearing something —or someone– in the room she shares with Sydney.

Here we’ll compress the long buildup of “C” (Sea?), as James calls her, straining to listen for some bumps in the night, to the moment when she knows the invisible but not so dead Griffin is in the room. Listen to how the sequence ends first with James confronting his daughter, whose instincts are to trust and point the can of pepper spray at something she can’t see but that she accepts as true because a woman, her godmother, reports it. James first disarms his daughter by questioning her sanity. Then he turns to C, shakes his head, extends his arms to embrace her and offers the psychological comfort to a friend he doesn’t believe and — by design of the stalker– quite naturally thinks is hysterical. Who seems temporarily, at least, deranged.

The most interesting aspect of Whannell’s update is the film’s sociology — which characters he chooses to do what. This Invisible Man has become a #MeToo story resting on top of racial reassurance. It’s the story of a white, contemporary, one-percent dot.com marriage of sorts — a Marriage Story, if you will –which has moved beyond talking and toward terror. Significantly, her terror — signaled by the menacing score by Ben Wallfisch — is mitigated by the sanity of the single parent, African-American working-class family that tries to love the demons out of her. It’s the Black family that’s not crazy, they know trouble, they’re most equipped for it. James is a single cop dad, he’s seen it all at work, he’s lost his wife and the mother of his daughter, and he’s willing to walk all the way up to the doors of his own perception and still be open to the presence of spooks in the attic of his friend’s mind, if not in the attic of his own house.

James and Sydney have a line that Cecilia eventually crosses, as the film picks up speed to hurdle toward the inevitable, and they have their doubts about bearing the burden of white craziness. But this is the #MeToo era, and The Invisible Man is a #MeToo story. The project is selling all these San Franciscans inside the story, and you in the audience, that something is rotten in the dot.com white house. Whannell’s Invisible Man asks that you might think about the politics of believing women when they report a crime against them, no matter how crazy you think they are.

The politics of Whannell’s film is streamlined and over-simplified: there are differences between Bill Cosby, Harvey Weinstein and Woody Allen, and their everyday counterparts in the real world. We’re only just starting to grapple with where women have weight in the discussion. Count The Invisible Man as part of that.