2025 78th CANNES FILM FESTIVAL SUMMARY

The official 78th Cannes Film Festival poster is actually two: Anouk Aimée and Jean-Louis Trintignant from both sides now of the final, elegant shot in Claude Lelouch’s 1966 now classic A Man And A Woman / Un homme et une femme

By Harlan Jacobson

Last year, the 77th Cannes Film festival had a playfulness about it built on the assumption that, while the world is always troubled, there was enough stability in it to play with ideas about money and class, gender and genre, sexism and body horror. Anora went all the way to the Palme D’Or and the Oscars. And it was joined by Emilia Perez and The Substance, all three mixing up body, gender and mob membership all the way to the Oscars. That’s not necessarily an evaluation of quality – though all three films were certainly quality films. It’s good for the films, good for filmmaking, and good for the film public.

In Cannes 78, it’s as if the team led by Thierry Fremaux, the delegue general, director of programming, compiled a list of films from Totalitarian Hell—all different angles on what happens when Totalitarianism in its various guises take over. Fremaux and company lightened up here and there with some films with heroes either saving or reinventing the world as it should be. But the curation was decidedly dark. This year’s Palme D’Or, Iranian director Jafir Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident, feels like the jury coalesced around a film that had the DNA of the year but not in the strongest concentration. Part of that calculus may be the protection the Palme might bring Panahi back home, but it would be the wise mullah who will recognize that It Was Just An Accident won’t have the wild ride Anora had last year.

If nothing else, Austin based director Richard Linklater gets the Medal of Honor for taking on Jean Luc Godard, the lodestar of New Wave French filmmaking, in his new film Nouvelle Vague / New Wave and bringing it in Competition to Cannes, center of the known universe for cinema. There is no US equivalence for audacity, maybe a French guy showing up at Yankee Stadium swearing he can hit 70 home runs. All the giants who revolutionized cinema are in this film about Cahier du Cinema film critic Jean Luc Godard making his first film, A bout de souffle / Breathless in 1960, that is the touchstone for the new stories and craftsmanship of filmmaking on the run ever since. It’s more than just a cameo parade of characters, though they’re all here – Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol, Jacques Rivette, and Eric Rohmer, for starters. It’s film aficionado fun to watch Linklater show Godard, then 29, played now by a thin and vaguely menacing Guillaume Marbeck, turning the camera on Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch) as waif Patricia and ex-boxer Jean Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) as Michel, the petit criminal. And doing it all on the fly.

Nouvelle Vague / New Wave

Shot mostly in grey and white, more than black, and in French and English, Linklater’s film sparkles with energy, but more controlled than Godard’s Breathless. The trick here is that Linklater’s Godard is wise at all moments through the tornado he’s whipping up to wreck filmmaking as we knew it, conveying Camus dressed up like Jerry Lewis, or Yoda like Pee Wee Herman. Watching his Godard think outside the box and chuck out years of ironclad limits, rules and conventions in a country that lives and dies by them, I had the odd thought that in Linklater’s telling, what Godard did in going rogue on Breathless was what the French always thought was American: jump the fence, innovate and keep moving. Unlike some countries we know, French institutions remain in place, and their cheese, wine and bread have also held for a thousand years. What Godard and his Nouvelle Vague confreres do in this film—one wonders if there were discussions about inviting it as Opening Night–is all the more remarkable not just for moving France forward, but for seeing and catching the wave of the modern that broke everywhere.

Will Nouvelle Vague play in the US? Yes, but probably not in a mall near you.

Spike Lee has been coming to Cannes since She’s Gotta Have it in 1986 and Do the Right Thing three Years Later. His fifth film with Denzel Washington (Mo Betta Blues, Malcolm X, He Got Game) and after an 18-year break since 2006’s Inside Man, is Highest 2 Lowest. Starring in Othello on Broadway, Denzel jetted in on his off day to attend the premiere, get an honorary lifetime Golden Palm, see a sizzle reel of his body of work showed to the opening night red carpet crowd, and then duck out as the house lights were going down to get home for Tuesday night’s show. The whole of it was a triumph as an event more than as a film.

Grumbly when previous films didn’t win in competition here, this time Spike couldn’t lose: the film was not in the Competition but outside it.

Spike’s film is based on a 1963 Akira Kurosawa policier, set in Yokohama, with Toshiro Mifune as a shoe company executive faced with a kidnapping crisis while planning a corporate takeover. Denzel plays David King, mogul of Stackin’ Hits Records, who prides himself on having the best ears in the business, a Dumbo penthouse, a foxy wife played by Ilfenesh Hadera, who likes the lifestyle maybe a little too much and which is upended when their son is kidnapped for a $17.5 million ransom by a wannabe rap thug, Young Felon, played by A$AP Rocky. The kidnapper-rapper thinks he’s concocted the perfect marketing scheme for which King ought to thank him. There’s a mix-up, however, that involves the son of King’s driver and childhood friend, played by Jeffrey Wright, which forces Denzel’s record mogul to travel a moral arc from the highest point – King’s glass penthouse in Dumbo to the lowest point, a basement apartment, A24, in the Bronx, which just happens to be the name of the feisty powerhouse film company that will release the film in August.

Highest 2 Lowest is more Grimm’s fairy tale than masterpiece, with Denzel as King sidestepping the ineffectual NYC cops to take up the chase around the city, where Spike lives and loves to film. Here Spike and Jeffrey Wright respond at a press conference to our question about the proposals for a national tax incentive and those controversial tariffs you’ve heard about to bring back runaway film and TV production:

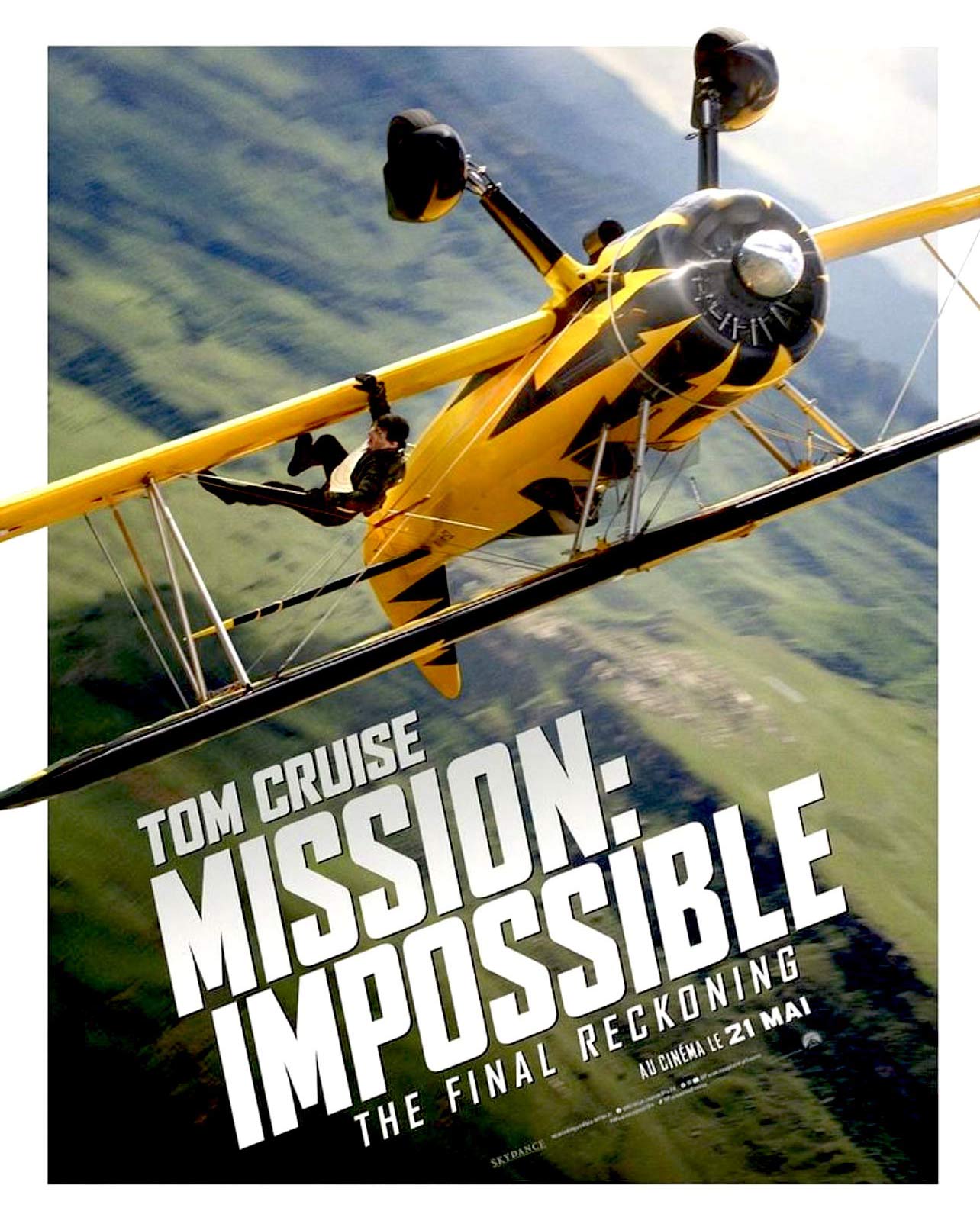

Denzel chases Young Felon all over the Bronx, in and out of subway cars, rocketing past Yankee Stadium in what is Spike’s cross between Kurosawa and Mission Impossible.

Contrast that to Mission Impossible: The Final Reckoning which Paramount showed, also out of competition here, to goose its release stateside this weekend. Unlike Top Gun 2, which started here, where you could ignore the thin plot to enjoy Tom Cruise flying fighter jets at something like Mach 100 upside down and sideways, you can skip this installment of Cruising. There’s endless yak-yak and set up to explain all the things that agent Ethan Hunt must do to save the world. There’s a Thing, and Cruise has to retrieve the Thing from a lost Soviet submarine beneath the polar icecap, where the Thing slips between nuclear missiles crashing around like bowling pins—a set piece filmed in a gigunda water tank with Cruise dodging the rogue missile props. Ultimately, Cruise ends up hanging off the struts of a Piper Cub and punching out bad guy, Esai Morales, who is after the Thing to rule the world. Otherwise, no matter the circumstance, he mainly laughs maniacally.

A piper Cub stunt, that’s what this is all about? Well, surprise: Piper cub wrecked, world saved.

Two Prosecutors, a Competition film by Sergei Loznitsa, Kiev born and USSR launched, the story sets up in 1937, during the Great Purge of Joseph Stalin, when a young district prosecutor arrives at the front gate of a prison that in longshot seems to extend all the way to the horizon. A letter written in blood by a prisoner claiming to having been railroaded into jail has come to the young district prosecutor, Kornyev. It’s the only one saved by an inmate tasked with burning thousands of inmate letters and smuggled out. In service to the justice promised by the Revolution, District Prosecutor Kornyev takes the letter to the top, Inspector General Viszhinsky, head prosecutor at the Ministry of Justice in Moscow.

Two Prosecutors, a film by Sergei Loznitsa

Based on a 1969 book by Georgy Demidov, a Gulag survivor, the story is about the betrayal of the Revolution by Stalin and by inference the fall of the Soviets in Putin. It is an ironic echo of Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, set in 1911, in which a Jewish worker sought a hearing in the Czar’s highest court. That ended better outside the Czar’s court in Malamud than it does with Two Prosecutors’ Stalinist Inspector General, who assesses the seriousness of the complaint brought to him by the idealistic, young prosecutor in a way the latter doesn’t grasp until it’s too late. Clearly, Loznitsa means in period to address the present.

Filmed in 4:3 ratio and in a color palate dialed down to shades of grey by cinematographer Oleg Mutu (4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days), Two Prosecutors is a letter sent to Cannes and the world about Russia now, not just Stalin then. After the Ukrainian invasion in 2022, Ukrainian born actor Alexander Kuznetsov, who plays prosecutor Kornyev, fled his career in Russian films and theatre for London. Anatoly Beliy, who plays the Moscow chief prosecutor. also Ukrainian born, abandoned a major career in Russian films and fled to Israel.They are now listed in Russia as Foreign Agents.

Dominik Moll’s Dossier 137 in Competition follows Stéphanie Bertrand, a woman police internal affairs investigator, as she uncovers a coverup of Paris cops brutalizing a young man during the Yellow Vests demonstrations that began in the Covid summer of 2020. Lea Drucker’s Internal Affairs officer, Bertrand, is the face of middle age frustration with justice denied and institutional coverup, protecting cops who on a better day were the first on the scene at the Bataclan concert hall slaughter. Officer Bertrand hits the male roadblock of a French judicial system that isn’t about to reign in its police.

A small stakes story that adds Moll (The Night of the 12th) to the voices in Cannes about the corruption of state power.

Seriously good but difficult was the out of competition The Disappearance of Josef Mengele by Kirill Serebrennikov, with German actor August Diehl giving full rein to the chief Auschwitz medical experimenter’s lifelong rage in exile in Argentina and Brazil that Nazism deserved victory not ruin. Serebrennikov, whose brilliant Limonov in 2024’s Cannes was completely overlooked, earns the body horror scene here that Julia Ducornau mostly exploits in her Palme D’Or winning TItane a few years back and again in Alpha in the Competition here this year. And so, in we go, as Mengele pries the body off the skeleton of a twin in the interest of Nazi eugenics, with Serebrennikov making up for deficiencies in the current educational systems around the world by reminding who Mengele was.

On the escape side of a chase story, Serebrennikov’s film never lets the audience lose sight of why that reminder is necessary: Unleash the beast, and this is where it goes.

Lynne Ramsay’s Die, My Love, in Competition, opened the door for Jennifer Lawrence as Southern mad housewife Grace to go completely feral in breaking out of her marriage to Jackson (Robert Pattinson) and the social expectations of motherhood and being a good, rural neighbor kinda gal. The politics of this latest film from Ramsay, who specializes in edge (Ratcatcher) and family (We Need to Talk About Kevin), don’t seem any further along than Diary of a Mad Housewife a lifetime or three ago. But as a post-partum film, it’s impossible not to admire just how far Lawrence goes in ripping the guts out of the new, perfect parenting of plans and playdates.

With Sissy Spacek and Nick Nolte, as grandparents who can spot crazy a mile away coming in on schedule.

Eddington by Ari Aster, set in May 2020 at the top of the Covid wipeout, was lined up to be a slam dunk with Joaquin Phoenix playing a gone-rogue New Mexico county Sheriff, Joe Cross, squaring off with Pedro Pascal as a by-the-book town Mayor, over everything from masks and social distancing, to the racial politics of Black Lives Matter, women (Emma Stone) driven nuts, fed up Native Americans, the arrival of a tech center – in short a garbage can of all the things that have made America crazy forever that’s turned into a powder keg over the last five years.

Eddington by Ari Aster.

When Sheriff Cross has had enough of all the pussyfooting around legal niceties, the long gun comes out on one side of the county line that results in a murder on the town side. Sheriff Joe claims control of a case he means to bury, but that’s not the way it’s going to go. Slogging forward in its escalation, the film starts with six-shooters and, in what is supposed to be surprising, moves up to war grade weapons. By the time he’s done with his fourth film, Aster (Midsommar) has delivered a 145-minute cartoon warning about Trump’s America just around the corner, folks. That might explain its selection, but overall it’s a tedious misfire that blows itself up and maybe the modern Western (Three Billboards Outsider Ebbing, Missouri) with it.

Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi’s It Was Just An Accident marked not his first film but his first appearance in Cannes since the mullahs lifted the house arrest imposed on him in 2010. Since they also forbade others from working with him during that period, he filmed himself in barely fictionalized stories over five films—all in secret. He was sent to prison in 2022 for asking about jailed director Mohammed Rasoulof (The Seed of the Sacred Fig) and released in early 2023 following a hunger strike. His time in Evin Prison in Teheran served as the springboard for A Simple Accident, which is a return to a broader fictional canvas.

The film sets a group of prison survivors on the road over the course of a day with a captive they believe is the intelligence agent who interrogated and tortured them during their imprisonment on political grounds. Is it him? If it is, what do they do with him? Blindfolded during their interrogations, they only have clues: his voice, the sound of his artificial leg, his smell perhaps. Panahi sets the investigation and argument up amongst characters who fall – or are dragged into – a van with the suspect bound and gagged in the back. It’s one marked by Panahi’s humor, to be sure, but the dynamic is unmistakably one embraced by Abbas Kiarastomi before him and then Panahi: the assembly of a cross-section of Iranians – a mechanic, a wedding photographer, a bride — approaching a small problem that measures where things are at the broadest political level. With a crazy stop or two along the way.

It Was Just An Accident by Jafar Panahi.

Having survived horrific state abuse, Panahi’s characters are faced with answering who they are now: people who trust in the application of good law or vigilantes with a good but imperfect case for revenge?

A Simple Accident is a good film, one civilized enough in its resolution perhaps to keep the mullahs at bay. It surely is the embodiment of filmmaking as courageous witness. But was it the Palme D’Or, which the jury awarded it for best film? Not by a long shot.

Sound of Falling from 41-year-old German director Mascha Schilinski, is a high art omnibus of four generations in a manor house in Germany. It weaves the lives of four characters, girls, Alma, Erika, Angelika and Lenka, growing up and coming of age in successive families in a farmhouse in Northern Germany over a 100-year span. Kudos to set design, lighting, camera and sound that summon the realist paintings of the late 19th century, where the interiors are dark and a little dirty, the exteriors are of heavy manor houses set amongst full season landscapes and clods of mud. The screen often feels as if covered in thick blacks and browns.

Sound of Falling directed by Mascha Schilinkski.

Overarching the four generations in the house, the men mostly act badly, which is to say in their own interests in a man’s world, and the women and girls chafe at the bit they share with the livestock. Schilinsky settles in for two and a half hours in a farmhouse that is low lit and suffocating, reflective of the heavy pall of the culture. You marvel at Schilinski’s palette, at the planning that went into the texture of each scene, as if deep paint troweled on canvas, as the women dissolve into the next generation

Far from the meadowlark joy of Little Women in England, the generations of women and girls here are the canvas for the brutishness of the German male. Sound of Falling isn’t mystical so much as a map of the unchecked authoritarian German character before it unleashed monsters.

Schilinsky’s film inspired respect in Cannes more than passion, which is how I absorbed it. Coming early in the Competition, it was the declaration that Cannes had gone dark this year. It ended sharing the runner up Jury Prize with Spanish director Oliver Laxe’s Sirat.

Set in Morocco, Sirat, out of the gate and into the desert, is an end of the world set piece. As Luis, Sergi Lopez, shows up at a freaky ravers dance in the Sahara Desert, with his 12-year-old son, Esteban (Bruno Nunez) and the family dog, searching for a missing daughter. Lopez’s Luis is a middle-aged, chubby white-collar guy driven mad in the search, having given up whatever middle-class life he was leading to end up in an encampment of desert-baked freaks in leathers, with no moorings except the sun and the music. Tattoos, a lot. Shaved heads, of course. Missing limbs sure, and teeth probably, I can’t remember. Histories of how this desert caravan of zombies left everything and nothing – the car radio interrupts with news of war – to follow the sun, they don’t look like they remember.

Sirat directed by Oliver Laxe.

When the Army shows up at the rave in this Cannes full of armies, Sirat seems like it’s taking a predictable turn into the usual antagonisms. But the film isn’t about that. In Sirat, the lunacy we can do to ourselves is so much worse than the military’s. Luis and Esteban manage an escape with the ravers into the desert on the trail of the next rave – who knows, the errant daughter might be there – on the Mauritanian border. That’s when Laxe’s road movie script, co-written with Santiago Fillol, makes a bold, eye-popping move equal to the legendary Hollywood joke about sending Lassie back into the burning house, but ups the ante into anything but funny.

Laxe’s script and direction never let up, leading his Everyman, and by extension the world, to the brink of an existential wipeout that is Luis’ and maybe our coming misfortune to survive. Fabulous techno soundtrack by Kangding Ray, great storytelling, big reach, beautifully shot by Mauro Hercé, Sirat had its naysayers in Cannes who probably correctly picked a nit about the believability of Luis’ response at the story’s inflection point in the desert. Oh, so what if no parent worth his sand would carry forward in service to Laxe’s bleak vision. The film got me when it slipped into reverse gear and never backed down.

The restoration of Istvan Szabo’s 1999 Sunshine is exquisite, beginning with the deeply saturated colors of sumptuous 19th Century Budapest. Now at 87, frail but present, Szabo had a full career of domestic films before Mephisto broke out internationally from Cannes in 1981 to win the Best Foreign Language Oscar, followed by Colonel Redl in 1985, both starring Klaus Maria Brandauer, both international hits. With Sunshine, Szabo ventured into making an English language film with Ralph Fiennes playing multiple generations over 100 years of a 19th Century Jewish merchant family that grew rich from bottling an herbal tonic. (I was never sure that it wasn’t an eau de vie, which makes more sense than “tonic.”) With key roles also for Rachel Weiss, Molly Parker and William Hurt, Sunshine struck me then as now as inorganic and misbegotten, though the intention was in keeping with Szabo’s sharp politics, to underline the false promise of Jewish assimilation into Budapest’s governing Catholic ruling class.

The film was produced by the Mr. Big of Canadian film production and distribution, Toronto-based Atlantis Alliance’s Robert Lantos, who accompanied Szabo to the Bunuel Screening Room, where the director was given a lifetime Palme. All very touching. Lantos remarked before the screening that on the plane home in 1997 he’d read the script Szabo had given him in Cannes, and when he landed called to ask how soon Szabo could start. “I thought then that it was important as a remembrance” of the Jewish experience in Europe, Lantos said. And then added, “I see now that It’s more of a warning about what is happening now in the country where I live.” That was an unexpected sit-up-and-take-notice moment.

There were also two new, neo-Jewish films, Scarlett Johansson’s Eleanor, the Great, a grab bag of Jewish stereotypes under a leaden layer of old lady schmalz, and Rebecca Zlotowski’s light take on Jews just being French Jews in the out of Competition Vie Privée (A Private Life), with Jodie Foster living a complex, cosmopolitan life of an American emigrée shrink in Paris, coping with a patient’s suicide, peeling back layers of her identity while being circled by Gabriel, her ex-husband played by Daniel Auteuil, who has settled into handsome late middle-age. Eleanor the Great marked Johansson’s debut as a director and was selected for the sidebar Un Certain Regard (A Certain Look) section. A crowd pleaser at Cannes, and likely when it has its US release, it’s an aging feminist addition to the Old Jews We Know and Love genre. In Tory Kamen’s script, Eleanor, played by June Squibb as if she read up on indigestion and how to give it, is a feisty, sassy, deep feeling, funny, wounded, triumphant old gas bag of Jewish cliches, in short stuffed kishke on a plate. (Better done in Going in Style in 1979 by Marty Brest with Art Carney, George Burns and Lee Strasberg.) I liked seeing Jodie do modern French Jew a lot more.

![]()

IMDb is the world’s most popular and authoritative source for movie, TV and celebrity content. Find ratings and reviews for the newest movie and TV shows. Go to IMDb »