A media star, imbued with a love of self even greater than his disdain for everyone else, parlays his on-air popularity into a rapid climb to political power. It is only when he attains his highest position does the full measure of his antipathy become apparent to his worshipful followers.

The year is 1957.

Elia Kazan’s A Face in the Crowd remains one of the most energetic and fascinating films of what we have come to think of as “the complacent fifties.” Never subtle – and all the better for it – it is an angry screed and loud clarion call to America to wake up, and to stop believing the attractive lies that push aside hard truths. In many ways, it is also a deeply personal statement; part recognition, part defense and possibly part mea culpa from two men who had a lot to answer for.

The anti-Communist witch hunts of the early 1950’s left few in Hollywood unscathed. Careers were cut short because of past political affiliations while those who “named names” would later find themselves ostracized. Of this latter group, few would face more scorn than director Elia Kazan and screenwriter Budd Schulberg. Both had renounced their past beliefs and provided HUAC with the names of “fellow travelers.” In 1954, the two men presented their rationale in On the Waterfront. The film won a bushel of Oscars including ones for Kazan and Schulberg as well as for Best Picture, a fact that has come to obscure its arguable message: Squealing is an act of public courage.

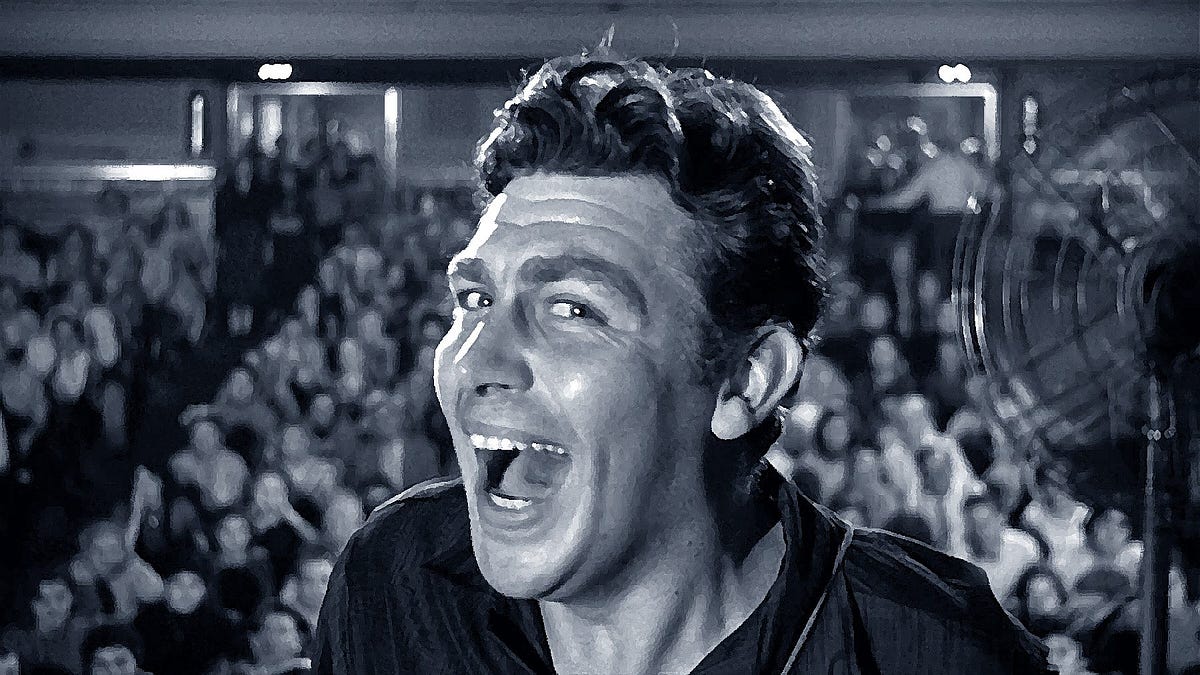

A Face in the Crowd blessedly avoids restating this message but does present a picture of an America that is easily duped by media moguls and politicians looking to take power. If Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront is viewed by Kazan and Schulberg as a born again crusader against corruption, A Face in the Crowd’s Lonesome Rhodes (Andy Griffith) is fascism incarnate, a profoundly corrupt, power-mad manipulator completely devoid of empathy and ideology.

Stretching from the dusty backroads of Arkansas to the impersonal canyons of Manhattan, A Face in the Crowd tells the story of Rhodes, a drifter and jailbird who happens to have the gift of gab and a gripping way of selling a song. Radio producer Marcia Jeffries (Patricia Neal) stumbles onto Rhodes in a jerkwater jail cell and sees a gold mine. Unfortunately for Jeffries, she has a streak of morality that will now come into conflict with her ambition and her growing love for her discovery. As Rhodes becomes more and more drunk on his newfound power, Jeffries must recognize her culpability and determine a way to stop him.

Kazan and Schulberg use the opportunity of A Face in the Crowd to examine the confusion and desperation that lay underneath America’s rush to conformity in the post war years. The America on view here is rural, insular and willing to believe any shyster who tells them that he feels their pain. These are people who accept the Bible at face value, always looking forward to that moment when the meek shall inherit the earth. Rhodes recognizes this, exploits it, and turns it into demagoguery.

In truth, the picture of middle Americans here is none too pretty, the uncomfortable concept of what are nowadays called “East Coast elitists.” This, though, is satire and as such it deliberately accentuates stereotypes to set up its targets. And there are plenty of targets here. Politics, media, and advertising are portrayed as different arenas drawn into partnership by one single overarching desire: Power. But it isn’t just institutions that are overcome with a social disease. The common people to whom Rhodes makes his pitch are greedy. Their greed, though, isn’t necessarily for riches or things. These people are greedy for a recognition that the mainstream never allows. Their desire to be recognized is a threat to those in power and Rhodes is clever enough to see this and to manipulate it to his own ends.

Griffith, in his movie debut, is not your father’s Andy of Mayberry. His Rhodes is loud, carnal and animalistic. For the only time in his career, Griffith is allowed to chew the scenery and he does so in ways that are frequently terrifying. Then again, this is a movie about casting against type. Neal, a forceful actress, believably plays Jeffries as a weak and willing accomplice in her own debasement. Walter Matthau is also cast against type as a pipe-smoking intellectual, a Madison Avenue Adlai Stevenson trying to survive in the lion’s den of early television.

Kazan directs everything with a manic feeling yet tightly controlled energy rare in his career (his only other example of this overheated style is the wonderful Baby Doll). The result is an interesting and wholly satisfying exercise in cinematic dexterity. A Face in the Crowd is filled with scenes that explode: a baton twirling contest featuring Lee Remick that manages to be both innocent and erotic, an explosive finale on the balcony of a garish penthouse, and best of all, a lunatic montage that skewers all of the movie’s targets within the context of a 1950’s-style TV commercial.

At A Face in the Crowd’s core runs a fascinating question that is unavoidable: In telling a tale of manipulation and the ways in which we allow ourselves to be duped, were Kazan and Schulberg critiquing themselves? If so, were they questioning being duped by HUAC, or by their once youthful idealism? Or, since the only character not duped by Rhodes is their stand-in, the intellectual Matthau, are they claiming to be above the naïve masses?

I first saw this movie twenty-five years ago. At the time, I loved its overblown nature, the ways in which it went too far in the name of satire. For me, it was a marvelously dark fantasia of political overreach, a warning about what could happen to our nation if we confused showmanship with leadership. Today, A Face in the Crowd provides a much different viewing experience. Like Tim Robbins’ similar 1991 film, Bob Roberts, it now looks like an act of extraordinary prescience. Yes, this is very much a satire aimed at the heart of its contemporaneous audience. But, like all great satires, it speaks to truths that are, for better or worse, universal.

Pack this one in the box marked “Everything Old is New Again.”