Film noir was the synthesis of a number of movements: an Americanizing of German expressionism and French poetic realism with a little Warner gangster film thrown in for good measure. More a mood than a genre, these movies hit their full flowering in the postwar years because the gloom on display perfectly suited the existential angst and accompanying social breakdown that inevitably follows global conflict. As the nation slowly got back its optimism the taste for these died out, ending with the double blast of Sweet Smell of Success in 1957 and Touch of Evil the following year.

So, I guess this means that society was doing fine, right? No, it just means that the noir had to figure out the new tenor of the times and adjust. It would do this with a bang in 1967 and that shot was fired Point Blank.

If the earlier noirs were about social dysfunction and breakdown, the neo-noirs were more about a distrust of the systems that rule our lives. Those aspects of life that the fifties told us to believe in were now looked at as sources of evil. The late sixties would bring on a decade-long cinematic questioning of our institutions that would drive the period that became known as “Hollywood’s Second Golden Age.”

Directed by John Boorman, Point Blank called into question the security we were all drawing from the supposedly paternalistic protection of the corporation by turning it into a criminal enterprise. This corporation uses capitalism not for advancement, but as a weapon against those who try to get more than the corporate leaders believe they are “entitled” to, and it turns the government into a fount of benign neglect at best, or an unindicted co-conspirator at worst.

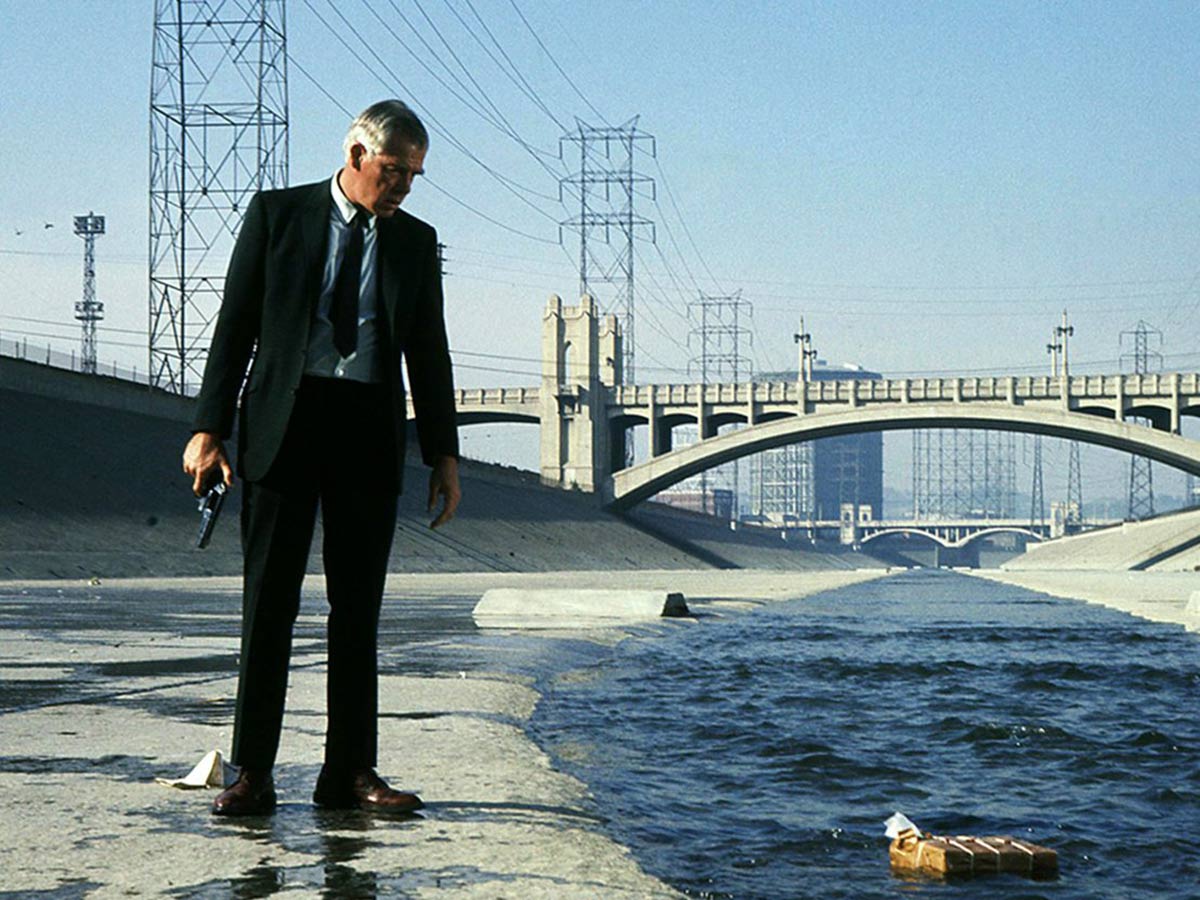

Our protagonist, Walker (Lee Marvin) is a criminal, pure and simple, yet we are asked to sympathize with his plight to recapture ill-gotten gains after he has been sprung from jail. He is brutally violent and not particularly bright. What universalizes him is something that every one of us who has ever had to call for technical support understands: When it comes to corporations, there is always someone above the person you’re talking to and, if you get through to that higher person, there is undoubtedly someone above them.

Walker is a victim of the then-brave new world of the corporate labyrinth. In this case, that corporation is Over-Organized Crime. Walker’s partner, Mal Reece (John Vernon), promised to hold onto their stolen money while Walker did the time. Unfortunately for Walker, Reece was recruited by the Syndicate which, in turn, absorbed the money. Now Walker is forced to punch up, to inflict mayhem on each rung up the corporate ladder until he finally reaches the Big Boss, Brewster (Carroll O’Connor) who, it turns out, doesn’t have any real power either.

Marvin’s Walker is a study in frustration, a hard man of limited intelligence who must somehow find his way through a minefield of sinister MBAs. His violence is not done in the calculated steps of a classic “man of action.” Even in past performances, particularly as the lethal hood in The Big Heat, Marvin had always been a smart operator who used violence to get what he wanted as well as to establish his big dog status in an alpha male world. His Walker, though, is an inarticulate man for whom violence is his go-to response to ever-deepening frustration. This is never more perfectly punctuated than in the moment when he bursts into the bedroom of his ex-wife. Finding her not where he expected her to be, he reflexively unloads his revolver into her empty bed.

Boorman’s technique throughout this film is dazzling, so much so that mainstream audiences of the late sixties were confused by his time lapses and flashbacks. Even today, it takes a few minutes to get the thread of where things are going. Once engaged, though, Boorman grabs us by the throat and refuses to let go. The violence is constant and staged for maximum impact with each act driving up the stakes in the story. By the time Walker finally gets to Brewster’s home in the hills, we have been set up for an intense confrontation. What we get is a darkly comic conversation that neatly wraps up Point Blank’s themes while also setting up an explosive climax set in the middle of a deserted Alcatraz.

The mood established by Point Blank is, if possible, even more bleak than the post-war noirs. This, though, is as it should be. Trying to replicate a mode that was no longer in step with where society had landed could only end with films that were creaky and old-fashioned (Harper, Tony Rome) or exercises in style rather than substance (Farewell, My Lovely). The sixties brought us civil unrest, riots, and quixotic and pointless wars. Point Blank may not address any of these directly, but it captures the zeitgeist in which such things happen.

This only leads to the obvious question: Where are the movies that will accomplish the same perspective for today’s broken times?