November 4, 2024 – Harlan Jacobson

Some years ago, I was with my family at the Marrakesh International Film Festival, where I took my daughter to the world premiere of Body of Lies, an espionage thriller by master intrigue and action director, Ridley Scott. Events this week brought that screening back to me.

Body of Lies had its premiere at Marrakesh because the British born Scott is a local hero. He helicopters to locations there from a house he keeps in country, where he films his action work in desert locations and at the country’s Atlas Studios. Body of Lies is pretty standard Scott warfare –definitely not in the Alien, Blade Runner, Gladiator or Thelma & Louise category. It’s based on a book by Washington Post columnist David Ignatius, whom I like a lot. It’s a Middle Eastern espionage thriller, set in Jordan, with a lone CIA agent (Leonardo DiCaprio) hunting down a head terrorist before dropping into a matrix of plots and counterplots, each resolving with someone getting it in the neck on the way to saving or blowing up the world. Back at headquarters in Langley, mission chief Russell Crowe is as cool balancing dinner and picking up the kid at school as DiCaprio is hot dodging incoming RPGs and running down dark alleys in ancient Araby. HQ in these things is always messed up, frustrating and running bass-ackwards, which is a staple of the genre.

What made this special? Every time the terrorists killed an American or American agent, the audience in Marrakesh would break out into wild cheers. “Kill his father, too!” Did I hear that (which turns out to be of some importance here later)? And as the frantic path to stop the terrorist ring from killing a lot of ordinary people and igniting global jihad see-sawed back and forth, the audience in Marrakesh would cheer the terrorist who killed this or that American pursuer. It was striking. Well, how could they not? Where you are and who you’re with defines what you see. And there we were… there… in what I had always embraced as the hazy, hashish destination on the Marrakesh Express of my mellow, peace and love brothers, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, who’d led me there. The audience at least was consistent: every time an American onscreen killed a terrorist in Body of Lies – the way the bad guys always get it by formula in John Wayne and Clint Eastwood movies – the audience at Marrakesh broke out into loud hisses and boos.

My daughter, then 13, looked over at me with great, big moon eyes and asked what the hell is going on here? It made me laugh, actually, and pulled me back from being lost in thought by how easily the film allowed opposite reactions depending on where it was seen. Her raised eyebrows clicked her terror into my focus: She was turned upside down by the haywire reaction of the nice people sitting next to her, In front of her, In back of her. I was lost in wondering whether Scott had cut the film differently for Arabic territories. In a way it didn’t matter whether he had or hadn’t – Scott Free Productions and Warner Bros. had a product designed to make money on either side of the fence. At work was the secret power of cinema that often gets forgotten – the audience watching it. In Marrakesh, Arab audiences screening Body of Lies seemed to have more room to hope and cheer before Scott brought down the inevitable hammer on terrorists and their collaborators, who were then still an agreed upon staple of cinema as bad guys.

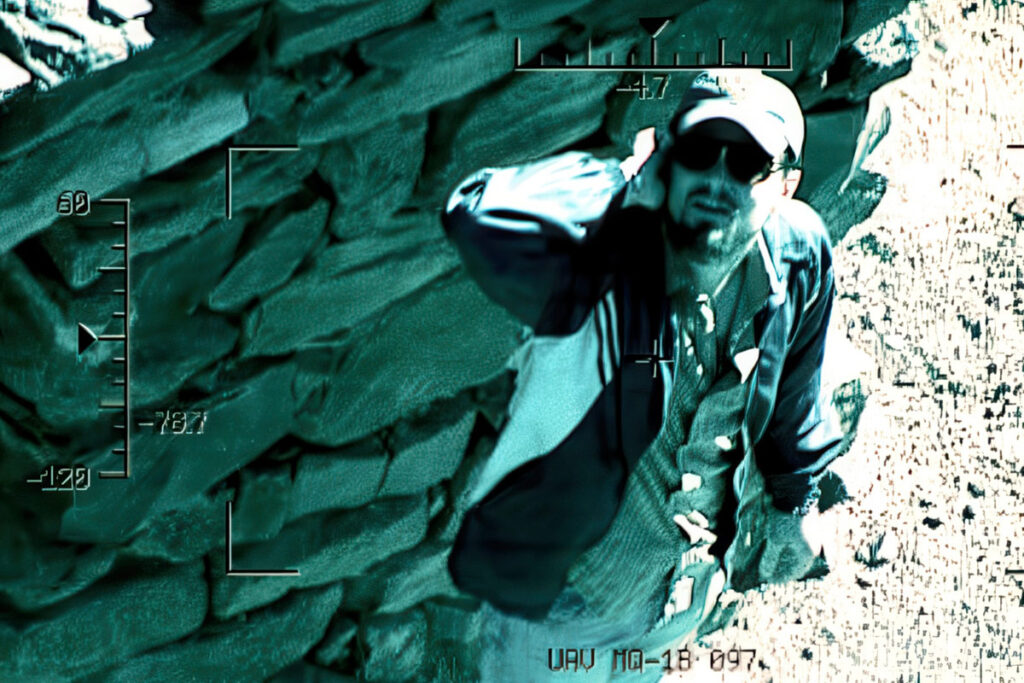

I was reminded of that screening this week by a story in the Washington Post* and media everywhere about how the cell phone video of Hamas terrorist Yahya Sinwar’s killing by a routine Israeli patrol in Gaza was interpreted radically differently by Israelis and the Arabic world at large. Sinwar died like all terrorists and tyrants, alone and in a hole (see Bin Laden, Khadafi, Saddam Hussein, and importantly to Israelis, Hitler). Or Sinwar died a martyr and a hero, fighting to the end, throwing a stick at his pursuers — in Hollywood terms, Jim Bowie and Sam Houston at the Alamo.

Sinwar Washington Post Article »

We rarely now speak of footage, which described film moving across a lens at 24 frames per second; it’s now the lightning-fast translation of digital code signaling pixels to turn on or off, just the way we want our reality. Sinwar’s cinema ending speaks to how the same images, taken from IDF cell phones – played to people on the different sides of this soul smashing conflict. On or off. It lands on an essential truth about images and storytelling. The power of cinema to mold and shape opinion – which governments and artists both assume and have historically fiercely battled over — overlooks one crucial element: audiences interpret, they see what they want to see. You think there’s one projector in a room, but there are often as many as there are people sitting in the audience.

Storytelling then, particularly with images is something of a guide. The artist’s guide to a place and time and people standing in for the meaning of conflict in war, in love, in fear, in joy and laughter, and in meaning itself. It may be artful or artless, the images may be by design or capture. But how we fill in the gaps of meaning is what the Cinema of Sinwar tells us about ourselves and the world we think we see so clearly.

IMDb is the world’s most popular and authoritative source for movie, TV and celebrity content. Find ratings and reviews for the newest movie and TV shows. Go to IMDb »