The early ‘80s Brown University Semiotics crew of Todd Haynes, writer-director, and Christine Vachon, producer reached back and pulled together a doc that more than simply captures the renegade Velvet Underground and its band of wayward angers, Lou Reed, John Cale, Maureen Tucker, Sterling Morrison and Nico and their ins and outs. It did something else which is difficult: without fawning — well, maybe with a lot of well placed reverence — it captures this particular group of flamethrowers’ fever dream bleed from the ‘50s Beats into ‘60s music and performance.

Not Hippies, mind you, the film speaks to the VU’s contempt for that, but the way forward from something more nihilistic into a truer art platform. It situates what must have driven everyone crazy at the time, what we now call Reed’s on the spectrum behavior when it came to work or almost anything and normalizes it as artistic furnace. When it comes to Reed starting out in Long Island, but ending not exactly like the kids that went on to be dentists or tattooists, the film lays it out: all that edgy homoerotica and sexuality carried forward by Reed smacked the culture like an 8-ball.

Using a split screen that alternates between forward narrative and archival portraits and films, the film anything but tonally hums along a clear line for an hour fifty minutes, bristling with energy and witness testimonies. It’s a hit parade of old hipsters: particularly the Welshman Cale, whose musicianship grounded Reed’s scattershot rock lyrics, avant-garde film lighthouse Jonas Mekas, who died two years ago and to whom the film is dedicated, drummer “Moe” Tucker, and former bandmates from his Syracuse days, Mary Woronov, who is particularly funny about how the VU showed up clad in all-black in pastel LA, Reed’s surviving sister, Merrill Reed Weiner, and film critic Amy Taubin—including pics of her as a sparrow who drifted into the scene for a time. Taubin zeroes in on what film’s frames per second does to the perception of reality, and we watch her time capsule segment doing the stare-into-the-camera-and-not-blink-thing that was a signature of Warhol’s Factory. I tried it afterwards back in my apartment on Face Time, because Taubin points out in the film it’s a skill. It is. It’s also the atom of acting.

“We weren’t part of the subculture,” Mekas says in one clip, “we were the culture.” It’s a cavalcade of Reed or Cale, Amy or Mekas and a dozen others on one side of the screen over time, while the film summons extraordinary archival vapors on the other to carry the narrative. It connects the visual dots and the universal cycle hum that the sound guys at the heart of the music rethink were all addicted to and made it their business to unpack that got repacked by later generations of musicians and filmmakers.

I don’t know what I don’t know, so if Haynes missed stuff or misweighted people and details, I can’t say on the fly. Since it’s about the Velvet Underground and extends what Haynes has done before, there’s no detour into the fraught Factory housing of Paul Morrissey, Joe Dalessandro and Holly Woodlawn as part of the scene. That, as they say, is another film, but I can tell you that Trash had an outsize impact on me as a suburban college hippie film nerd. When I saw Trash at the Bryn Mawr Theatre—of all places, in those days–which has now become the great Bryn Mawr Film Institute, the light went on about what was possible on film in a way that my studies of the bad boys of 19th century literature remained abstract. Haynes’ and Vachon’s Velvet Underground glories in the Baudelaire and Rimbaud of all this and manages to pull off a slight dig at the more market-driven Dylan as if Reed and Co.were a downtown S&M shop talking smack about Bloomingdales.

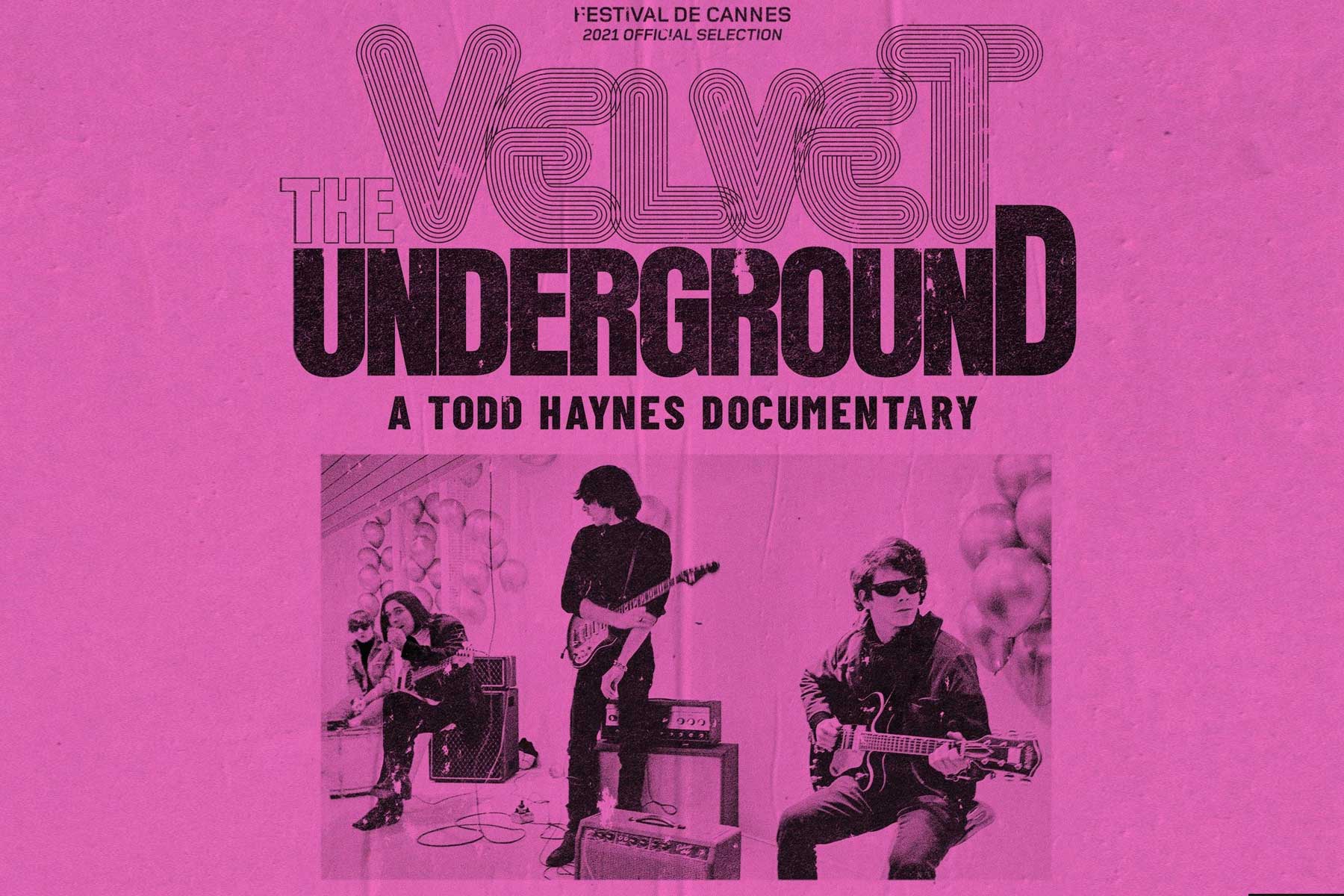

Like other careless folk of my time, I have a takeaway: I wish I hadn’t given my Banana album to my son. Well, it’s in great hands, as I prepare my eventual exit as a suburban recluse: he has a turntable, after all, and I don’t. Which says something about both of us. This doc sets the tempo for 2021. Due out in theaters and online from Apple, Oct. 15.

À LA MOUCHE / À LA VOLÉE (ON THE FLY)…

CANNES, Friday, July 9 –

By Harlan Jacobson