As we head into the holidays, there’s a sleigh full of new films that either have opened or are opening before the end of the month. Some are in the Oscar hunt and need a week in theatres to qualify, all are hoping they’re good enough to attract your attention after you’ve cleaned up the wrapping and before you get to the champagne.

Appropriately, or maybe inappropriately, are three films arriving in the category of Resurrection Cinema, Films rising from the dead — the long dead in this case. If Beale Street Could Talk, based on a 1970’s novel by James Baldwin, couldn’t be timelier, in part because the problem of being a black man facing a white justice system persists. I first saw Beale Street at the Toronto Film Festival at its premiere at the Princess of Wales Theatre, a beautiful downtown venue, before a huge, adoring crowd with filmmaker Barry Jenkins—he of Moonlight Oscar fame—and the cast, including the leads Stephan James as Fonny Hunt and Kiki Layne as Tish Rivers. Beale Street pits two minorities against each other, a Puerto Rican woman who misidentifies a young black man as her rapist, in the teeth of a white justice system that sees black guilt first, innocence last. While still gripping, the film’s excellent locations—chosen by my son, I must add—don’t mitigate the sense of being a filmed play in its various interiors. Like the revival of To Kill A Mockingbird on Broadway, Beale Street focuses on a black man wrongly accused and convicted, touching on white fear of black sexual power. By sheer accident of timing, both works land a year into the MeToo movement and make the historic case for due process exactly at the moment when MeToo has shifted the ground and seeks justice for allegations made in the court of public opinion. If not perfect, Beale Street is worth your while for the milieu, the discussion and the performances.

Talk about resurrections, The Other Side of the Wind by Orson Welles is one of the greatest constructions of an unfinished work, since Deryck Cooke’s assemblage of Mahler’s unfinished 10th Symphony in the 1960s, 50 years after Mahler died. OSW is a fitting if tragic end to Welles’ career, drawing the last of his great men, put on the cinema map in 1941 by his Charles Foster Kane, played by the young Welles at the top of his power. Citizen Kane transformed the way we understood character and see films.

In The Other Side of the Wind, John Huston plays Jake Hannaford, a film director at the end of his career, broke but not quite yet broken, as he tries to finish the film he’s made, called The Other Side of the Wind—the rough cut of which both Hannaford and we try to watch at Hannaford’s 70th birthday and the film’s LA wrap party. The film’s narrative arc follows Hannaford as he and his actor, Brooks Otterlake, played by Peter Bogdanovich, who’s championed both Welles and this film for 50 years, consider the film and filmmaking sitting on top of the shifting tectonic plates of the 1960s. A raft of actor resurrections in this film: Huston first and foremost, then Susan Strasberg, Oja Kodar, who co-wrote the script, Lilli Palmer, Edmond O’Brien, Mercedes McCambridge, and with party cameos by new wave revolutionary directors Claude Chabrol, Paul Mazursky, and Dennis Hopper among others, nearly 50 years ago.

Of course, the film mirrors the crash and burn of Welles, by then persona non grata in Hollywood, who shot the film between 1970-76 but constructed only some 40 minutes of it by the time he died in 1985—leaving 100 hours behind in cans in a vault in Paris. Relating the story of how this film came to be rescued would take longer than its two hours, but it is a miraculous resurrection pushed over the finish line finally and ironically by Netflix, which has served notice on the now old New Hollywood that it means to challenge the theatrical model of seeing films. I imagine Welles’ holy spirit having at least a laugh over that. The film, however, is not really for the casual filmgoer, but it’s a great time capsule.

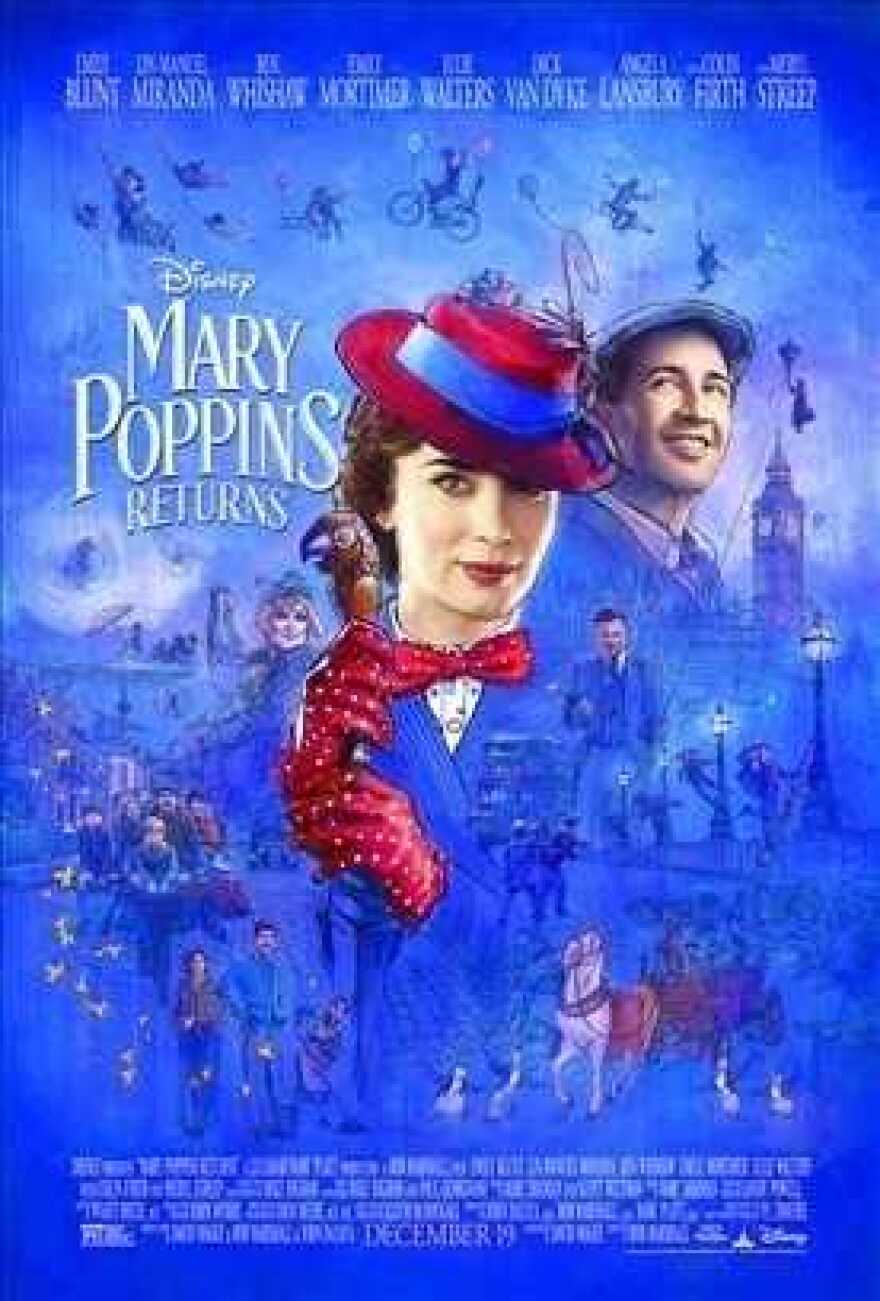

The third in our Resurrection series, is Mary Poppins Returns, which updates Mary Poppins, the 1964 musical with Dick Van Dyke and Julie Andrews as one of the last gasps of the old-style Hollywood musical. Andrews appeared in The Sound of Music a year earlier—before things turned Hair-y. In Rob Marshall’s Mary Poppins Returns, the Banks family — a generation removed – is once again broke enough to lose the great old house on London’s Cherry Tree Lane. Are we able to see through the plight of such economically useless aristocracy? We press on. That’s when Jack the chimney sweep, who apprenticed to Bert, Dick Van Dyke’s sweep, pulls the new Mary Poppins down on the tail of a kite, to do her nanny magic on the kids and a kind of de facto stand in for financial planning and lawyering to help widower Michael Banks, played by whisper lightweight Ben Whishaw, and the entire family out of an insolvency crack.

What could go wrong here? One, Lin-Manuel Miranda is a squat little fireplug compared to Dick Van Dyke’s double-jointed arms and legs, string bean-like chimneysweep in Mary Poppins, which traced itself back to Ray Bolger’s 1939 scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz.

Two, Blunt can’t dance. I like Blunt. She’s hot. In fact, there’s a lot of Blunt bluntly making blunt eye contact with all the adults in the audience, giving us haughty looks over her shoulder in insert shots that toggle between her sado-masochistic bedroom stare and her high heeled footwear that says, “Aha, I mean you, daddy.” You could call the paddy wagon on the film critic, but this is what Rob Marshall did in Chicago, for which he won an Oscar, when Catherine Zeta-Jones couldn’t dance, by substituting a lot of editing of machinegun close-ups, mid-shots, and heels shots. Mary Poppins Returns does have some big scale production numbers, “Trip A Little Light Fantastic” for one, marked by a frenetic relentlessness, where at least real dancers zip around the stage like electrons in period garb, enveloping and disguising for the moment that Miranda is a lump and Blunt is a lox. A smart and hot lox, but there it is.

In short, it ain’t the original Mary Poppins, whatever you thought of that, which seems graceful and effortless by comparison. It’s better than a lump of coal in this year’s stocking and will just have to do. With a spoonful of sugar, after all, the medicine goes down.

Read Full Review at WBGO.