Pain and Glory is writer-director Pedro Almodóvar’s 21st film in a career spanning nearly 40 years. I caught it at this year’s resplendent Toronto film Festival, but it touched down briefly at the ongoing 57th NY Film Festival, which ends this weekend after 17 days with a reprise of some of the festival’s 40 films.

There’s always been something so personable about Almodóvar that almost no one calls him Almodóvar. Everyone calls him Pedro, as if they know him. His films seem about you: contemporary city characters muddling through complex personal relationships and careers, usually with a gay inflection, almost always with stripes of humor, irony, a maniacal obsession or two, an embrace of hothouse sexuality, bad behavior, seemingly unreconcilable impulses, great music and jelly bean color.

His early films, Pepi, Luci, Bom, Law of Desire, Matador mixed sexual rebellion as a political rejection of the Franco years with a layer of camp humor, as if Pedro was a Spanish wingman for John Waters. But Woman on the Verge of A Nervous Breakdown, with his then favorite Carmen Maura, was a breakout hit and made him an art household name and marked his growth as a filmmaker toward the mainstream. It was followed by Tie Me Up, Tie Me Down and High Heels , which were sexually playful, of course, but marked a steady path that has been less rebellious, more nuanced and, by dint of more experience as a filmmaker and more resources, better crafted.

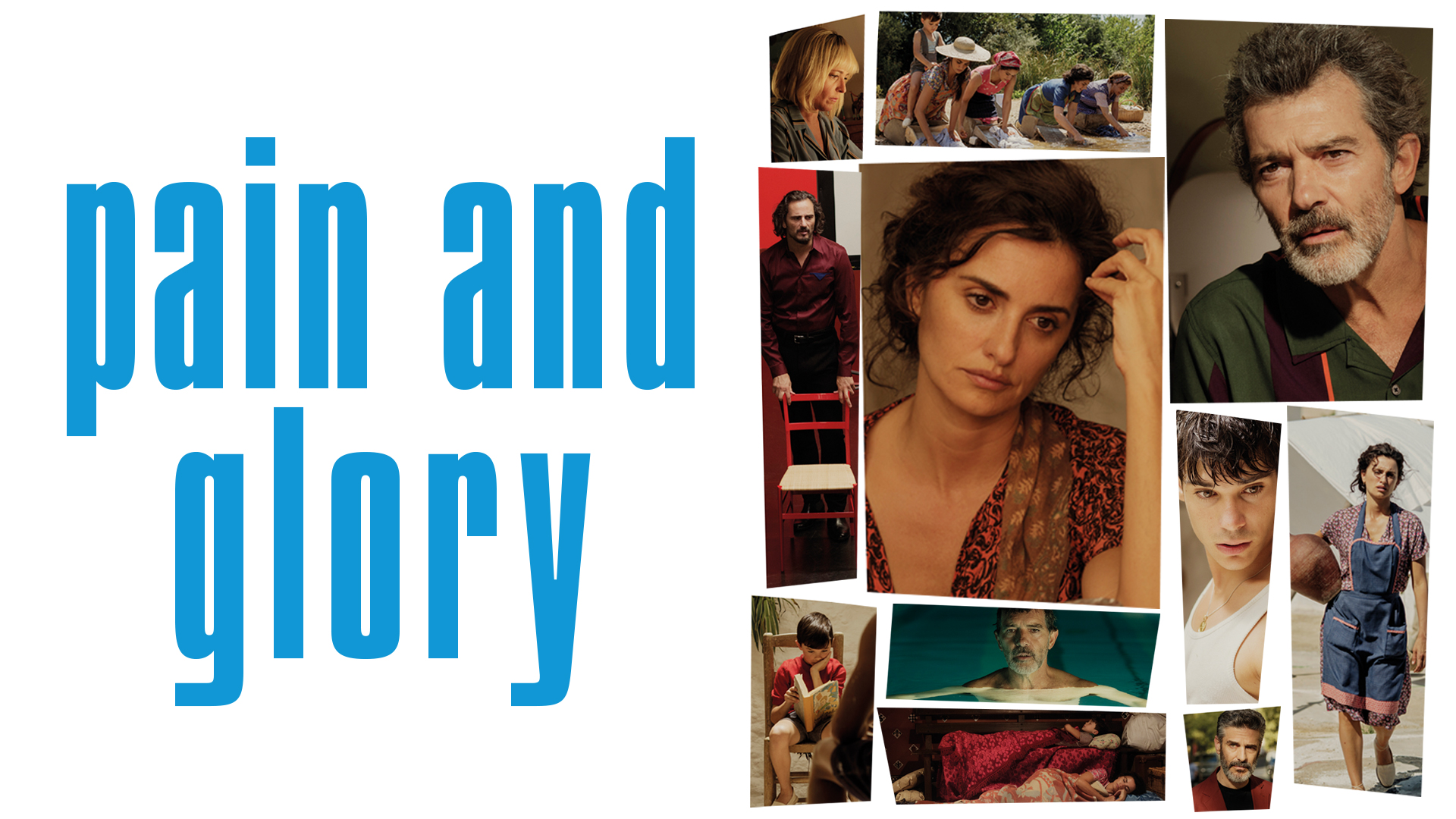

Now, at 70, which Pedro turned two weeks ago, he delivers Pain and Glory, starring Antonio Banderas, who goes all the way back to Pedro’s Labyrinth of Passion in 1982, when he played a gay Islamic terrorist in a camp Almodóvar sex farce. Banderas has since become a major star, made a lot of studio stuff that’s never been as good as the four or five roles he’s done for Pedro, and certainly not as good as he is here as Salvador Mallo, a self-spooked film director at 70, wrestling with all the various demons from the past that haunt his way going forward. It just so happens Salvador lives in an apartment that’s a direct mockup of Almodóvar’s Madrid digs, his hair has been styled to match Pedro’s—and his clothing is taken from Pedro’s closet.

Thanks to his cinematographer (Jose Luis Alcaine) and art directors, the film is suffused in Almodóvar color that branches out from the white sheets hung on the tall river grass to dry by the 9-year-old Salvador’s mother – played by Penelope Cruz, another Pedro talent from his early years who has become an international super star. The small family moves into a white cave in Valencia that his father has found for them to live in. Everything in Pain & Glory starts in white and fans out in color – from the innocent 9-year-old Salvador to the burned out 70-year-old director digging up his first actor, Alberto Crespo, star of his first big movie, Sabor / Taste, from whom he’s been estranged for 32 years over a falling out they had about interpretation. Crespo , played brilliantly by Asier Etxeandia, took the character on a downbeat, which jived with his once and current drug habit. When he finds Crespo now, holed up in a seaside flat on the edge of nowhere, Mallo, the director in existential crisis, dives right into the actor’s drug stash—only as a voyager, on his way elsewhere, with unexpected encounters with an old lover, friends, a watercolor by an obscure object of desire from his youth, his now 90-year-old mother, and the betrayal and looming breakdown of his body.

Welcome to Pedro’s life tour at 70. Which Pain and Glory undertakes with fanfare by composer Alberto Iglesias, as Almodóvar truly becomes Pedro at his most vulnerable and personal with his audience. Having acquired the film before its debut at Cannes last May, Sony Pictures Classics opened it in theatres where you can see it now following its NYFF screening.

The NYFF reprises films all weekend, where you won’t likely see its big get, the sold out screening of Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, out later this season via Netflix, but might catch some of the five titles the indie distrib Kino Lorber has in the festival, including Beanpole, the haunting film about Leningrad in the autumn of 1945, Young Ahmed by the past Palme D’Or winning Dardennes Brothers, a dance doc about Merce Cunningham from Magnolia pictures, and Saturday screenings of Netflix’s Marriage Story with Adam Driver and Scarlett Johansson having a fatal case of separation anxiety, Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow from A24, Portrait of A Lady on Fire from Neon, and a free Saturday eve screening of the doc, American Trial: The Eric Garner Story Saturday night at 6 at the Walter Reade.

Finally don’t forget Joker which opened here after a one-shot stop at the festival before it goes out on Netflix later this fall.

The Todd Phillips film has touched off debates between the Woke Crowd, who say they aren’t going to see it because “it sends the wrong message,” whatever that is, the enraged DC fundamentalists, the film critics who are divided about it and its unexpected fans. It’s not a DC Comic book film. The character, wounded, gradually enraged, played both heavy and lighter than air by Joaquin Phoenix — who is now the one to beat at the Oscars in a loaded category — was birthed at DC but has been liberated from its origins to take on the political shading of Trumplandia, and never more so than in the last third of the film. I wouldn’t call it self-important, as many film critics do, but beguiling and ambitious. I didn’t want to see this film at Toronto, but compelled out of professional necessity by its win of the Golden Lion at Venice, dragged myself to see it.

It couldn’t be more current. I don’t think Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck is any old generic Little Man, but instead taps into white working-class rage – justified or not — as the unlikely script, co-written by Hangover director Todd Philipps, seduces the viewer with fear, anger and empathy. No mean feat that. And all very much part of the character development, from whence this Joker starts to where he arrives at the bonfire of the verities.

Joker’s wrath which sets off a Hieronymus Bosch like rampage, is not a prescription for violence, of course, which is the usual simplistic reading that inflames the righteous, but a description of a character that goes back at least as far as the programmed assassin in The Manchurian Candidate, travels forward as the lone assassin Travis Bickle in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver, and now gathers at rallies in red MAGA hats saying they’ve got guns they know how to use if they have to.