Respect is the latest in the cascade of musical biopics. It follows the distant 1972 Lady Sings the Blues about Billie Holiday, through to the 2004 Ray, about Ray Charles, to the great Get on Up in 2014, with Chadwick Boseman as the hardest working man in show business, James Brown, to last year’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, with Viola Davis showing who was boss first. [Tune in here for the broadcast version of Harlan’s review of Respect.]

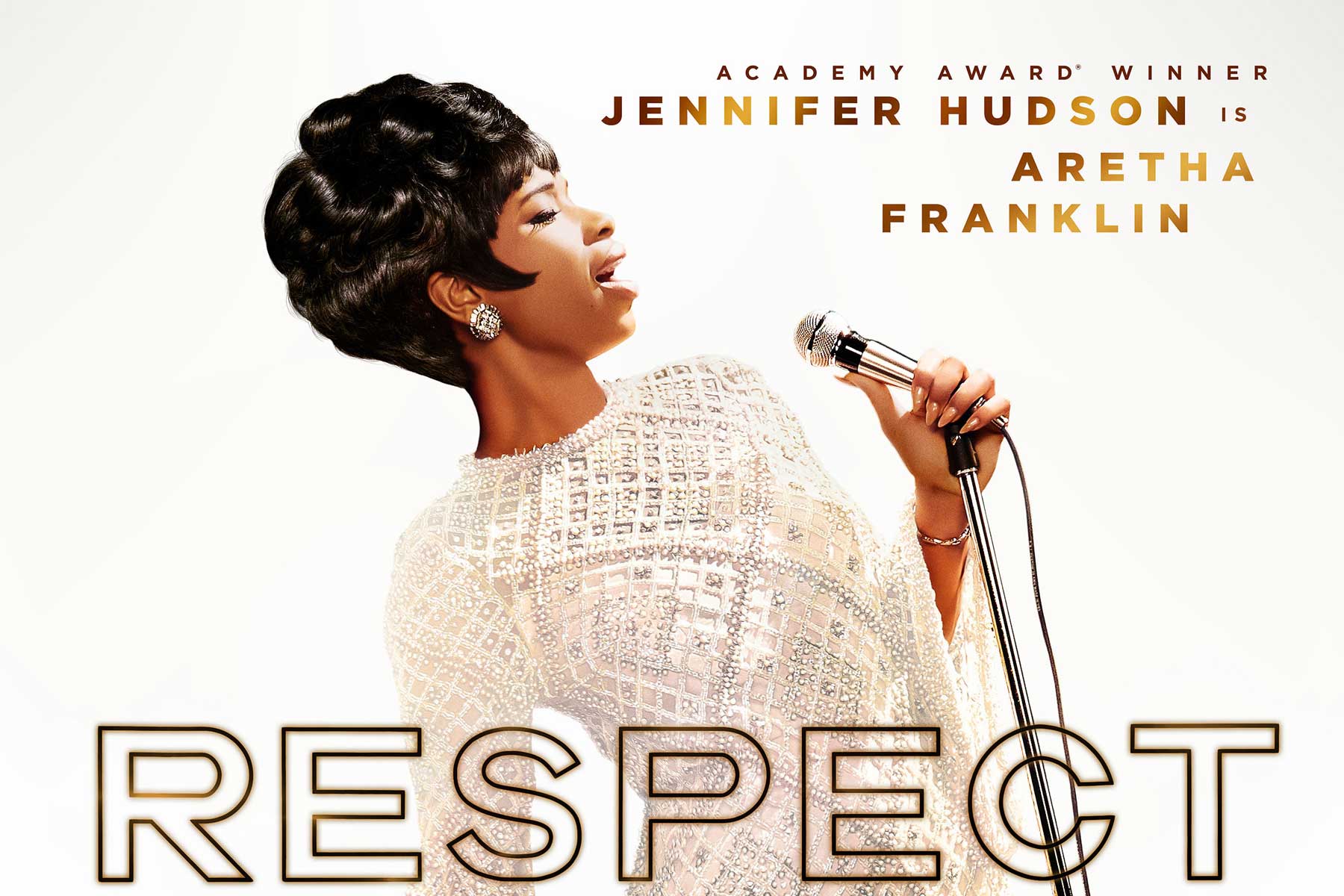

The strength of Respect is Aretha Franklin’s pure musical force, rendered here in a number of live singing sessions by Jennifer Hudson — the American Idol superstar befriended by Franklin who reportedly urged Hudson to play her, and who sang Amazing Grace at Franklin’s funeral in 2018. Franklin’s ghost outshines the storytelling here by Tracy Scott Wilson in a first film directed by South African – US stage and TV director Liesl Tommy.

It covers a 20 year span from Franklin at 10, awakened apparently regularly by her charismatic father the Rev. Dr. C.L. Franklin, head of a Baptist church in Detroit, to sing gospel for rooms full of his smart set friends, variously Sam Cooke, Ella Fitzgerald, MLK Jr. Mahalia Jackson and Dinah Washington, all of whom respect her as “10 with a voice going on 30.” The Reverend is plugged into the black and white power structure — a role given to Forest Whitaker to play as clued-in professionally and clueless personally about his wife, Barbara (Audra Macdonald), their daughters, and the adolescent Aretha impregnated at 12 by one of the unnamed guests. The Rev. Dr. Franklin does get her to NYC and John Howard at Columbia Records, who at Daddy’s direction shoehorns her into being a black Judy Garland singing 40’s standards, and fails. It’s Dinah who knocks her flat one night in a club after Franklin starts the first bars of “What A Difference A Day Makes,” I believe, and tells Aretha to find her own damn voice.

It’s 80 minutes into Respect’s nearly 2 1/2 hours when we eavesdrop in on how Aretha Franklin re-tooled Otis Redding’s version of “Respect”—a black man asking for respect at home from a woman in a white world that had none for either. Franklin’s version was understood at least as much about blackness as it was about ‘70s Feminism, which repurposed it as an anthem and maybe deracinated it depending upon where you came from and when. In Tommy’s film, Franklin spends the night up at the piano playing with the lyrics, waking her backup singer sisters Carolyn and Erma, whom she hooks with do some “just a Little bit” even before they rub the sleep out of their eyes.

That’s the trajectory, of the film, Aretha finding Aretha. And of course, she does find her voice, which Hudson, somewhat higher and thinner than Aretha in her sound, nevertheless powers pretty amazingly through Aretha’s career. Which was saved by Jerry Wexler, rendered here by Marc Maron in a script that calls for practicality replacing personality. Wexler, in the background of a number of musical biopics himself, deserves his own film. It’s Wexler who engineers the legendary meetup between the lost black soul singer to be and the dead head white rebel band in 1967 in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

Respect is no stranger to biopic conventions, in fact it’s a compilation of all of them: the well placed pieces of advice that reverberate years later — Your daddy don’t own your voice, only God does; Don’t let nothing come between you and your music, music can save your life. Then there’s the hit parade of stops that rise two steps up, one step back, and fall three at a time: The troubled home, the gifted voice, the shaky uncertainty, the talent, the wrong path, getting swept up in civil rights — the script papers over the chasm between Dr. King and the black panthers and Angela Davis – Franklin’s rocket rise to world fame, Madison Square Garden, Radio City Music Hall, Cobo Hall on Aretha Franklin Day back in Detroit, on to a European tour, and her inevitable fall, in Aretha’s case brought on by a bad husband she jettisons, the relationships and values she abandons, and of course the bottle. She fires everyone, including her backup sisters, Carlyn and Erma, until she falls off the stage drunk in Columbus, Georgia and lands back in the lap of James Cleveland (Tituss Burgess), the former music director in her daddy’s Church, who brings her back to gospel and the breakthrough Amazing Grace LP, the best-selling one of her career.

I wish Respect were a better film. I wish it looked better; everything in the background color palette is the color of oatmeal, perhaps better for the costumes to stand out and the music to shout out. It’s best when it’s real: Aretha singing live in the end credits, old, lauded and loved. The late director Sydney Pollack had his camera in the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in LA in 1972 for her return to Amazing Grace, the archival footage of which was edited down to an hour and a half and released as Amazing Grace three years ago first at the Tribeca Film Festival and which you can see now on Hulu or Amazon Prime. I applaud MGM/ UA for taking this Respect out into theatres. But if you’re going for a night out to take it in as a guilty pleasure — and no question about it, be moved by Jennifer Hudson past the cliches of the storytelling — do yourself a favor and later watch the real thing, too, Amazing Grace, Pollack’s doc footage of Aretha herself. You’ll increase your respect more than just a little bit.