The strongest among the films I caught up with were mostly those about the great disconnect, as if there’s just some information missing in what’s going down between characters onscreen. There’s no great theme at work here, or maybe not consciously, since what’s on display is as much a function of what got made during the last two years of social shutdown as what got chosen by festival programmers. Sometimes the characters onscreen wear masks, particularly if they’re the hyper conscious US indie Sundance staple of earnest questing scions of the middle class, sometimes they don’t, if they’re about war in the Ukraine. There’s plenty of injury in this year’s crop of films, injury arising out of the major actors in the stories hiding the football from each other, in fiction or documentary.

There’s an endless supply of New Jersey Bat Mitzvahs in Cha Cha Real Smooth, a US indie that Apple just bought for $15 million, written and directed by Cooper Raiff. Raiff also plays the lead role, Andrew, who returns from Tulane—that’s acutely observed about this demographic– to his Englewood NJ parents’ home to figure out what he wants to do next. Pretty au courrant. Raiff as his own hero, Andrew, starts out by being what used to be called in Yiddish the tummeler, tumbler, but now is called the party starter, the guy who gets every body in motion. He goes on to break all records on the male sensitivity meter, even for his generation, when he gets up close and personal with a depressed single mom played by Dakota Johnson and her autistic 13 year-old daughter.

The other US indies in the Sundance sensitivity sweepstakes are haphazard in the writing and direction departments: Sharp Stick by Lena Dunham, features Kristine Froseth as a wide eyed sexual adventurer with hints of Voltaire’s 18th Century adventuress, Candide ( a comparison suggested by the design of the end-credits), who makes her way down an alphabetized sexual perversions list that rhymes with bucket. More overtly in the spirit of the late Reader’s Digest, is actor turned director Jesse Eisenberg’s When You Finish Saving the World, with Julianne Moore as an aging 60s-style activist who can’t see much worth in her folk singing dud of a son played by Stranger Things star, Finn Wolfhard. Life in these 2022 United States. Oh, good grief.

They do these films in England differently, two about adults of a certain age who are solitary figures, cut adrift from family and history, looking for love in all the right places. Sophie Hyde’s Good Luck to You Leo Grande, with Emma Thompson, follows a middle-aged teacher on a bucketlist quest for an orgasm with a young male sex worker. The difference between Emma’s English teacher’s sexual bucket list and Lena Dunham’s should be noted. And a film titled simply Living by South African director Oliver Hermanis from a Kazuo (Remains of the Day) Ishiguro’s script, is about a 1950s London bureaucrat, played by Bill Nighy with barely a heartbeat as a man in a bowler hat, in a sea of bowler hats, who one day quietly wakes up and decides to make the broken system of endlessly circuiting paperwork between departments actually work. And, oh yes, try a night out on the town.

Rory Kennedy’s doc, Downfall, the Case Against Boeing, just makes you mad at corporate America all over again, which began a long time ago with Big Oil, then Big Auto, Pharma, Agriculture and extending now to the premiere US aircraft company, Boeing, that knew about and covered up the design flaw that dropped two of its latest model 737-Max planes out of the sky, a Lion Air jet out of Jakarta in 2018 followed a few months later by an Ethiopian Air jet out of Addis Ababa. All in a rush to production that stops just short of figuring in settlements as part of the cost of keeping market share. Eva Longoria Baston’s La Guerra Civil about the 1990’s matchup between warring Mexican light welterweights — Julio Cesar Chavez from Mexico and Mexican American golden boy Oscar de La Hoya from LA– punched my ticket, lights on not out.

There’s no sidestepping We Need to Talk About Cosby, Kamau Bell’s 4 hour, 4 episode recounting of the puzzlement that is Bill Cosby, which launched at Sundance and goes out over Showtime starting this Sunday. Jan 30. The spine of Bell’s narrative is whether one can separate the art from the artist. His witnesses —women who crossed Cosby’s orbit, folks of note, academics, comedians – are divided over this question, which has come up enough of late to evade an easy answer on a case by case basis. It does lead Bell to his conclusion: the great and good Bill Cosby paradoxically remade the black world, and ultimately all of America, as a place where the bad Cosby was finally destroyed. Even if he got out on a legal technicality last June.

I liked – not loved — Call Jane by Phyllis Nagy, who wrote Carol and turned director of this story about a sub rosa abortion clinic that operated on the South Side of Chicago in the 1960s. Scriptwriters Hayle Schore and Roshan Sethri re-establish the safe health care context of the original drive to make abortion legal that culminated in Roe v. Wade in 1973, an event that puts the Jane clinic out of biz and ends the narrative of the film. The architecture of the characters is a little too neat: Sigourney Weaver is a tough talking alley cat, Elizabeth Banks a suburban housewife without a thought beyond dinner whose pregnancy in her late 30s is life threatening. It’s also life changing. Of course, she has a clueless lawyer husband (Chris Messina) and an adopted daughter. The abortion “doctor” (Cory Michael Smith) looks more like a sex industry worker than Yale, and the black woman clinic worker as the civil rights conscience is there to say “What about us?” All of which contribute to the sense that the fiction here has been better designed than Tia Lessin and Emma Pildes’ documentary called The Janes, based on this same clandestine Chicago abortion group. Battle over, everyone thought in 1973, but clearly not.

Klondike, a Ukrainian film by Maryna Er Gorbach, is set in 2014 in Donetsk as the Donbas civil war gets underway between pro-Russians and Ukrainian nationals. Couldn’t be timelier. There’s a certain former Soviet film style in which everyone yells at the highest register for 100 minutes — as they do here. Irka is pregnant, Tolik, her husband, is incapable of holding two sticks together, the walls get blown out of their farmhouse, they lose the cow, men are boobs or barbarians, and the worst keeps getting worse. Somehow through all of this women keep giving birth. I hated watching Klondike: it’s tragic, it’s that special brand of black existential fatalistic hell humor set in a landscape of Rothko paintings. But after living with it inside my head for a few days, it’s perhaps the best film I saw.

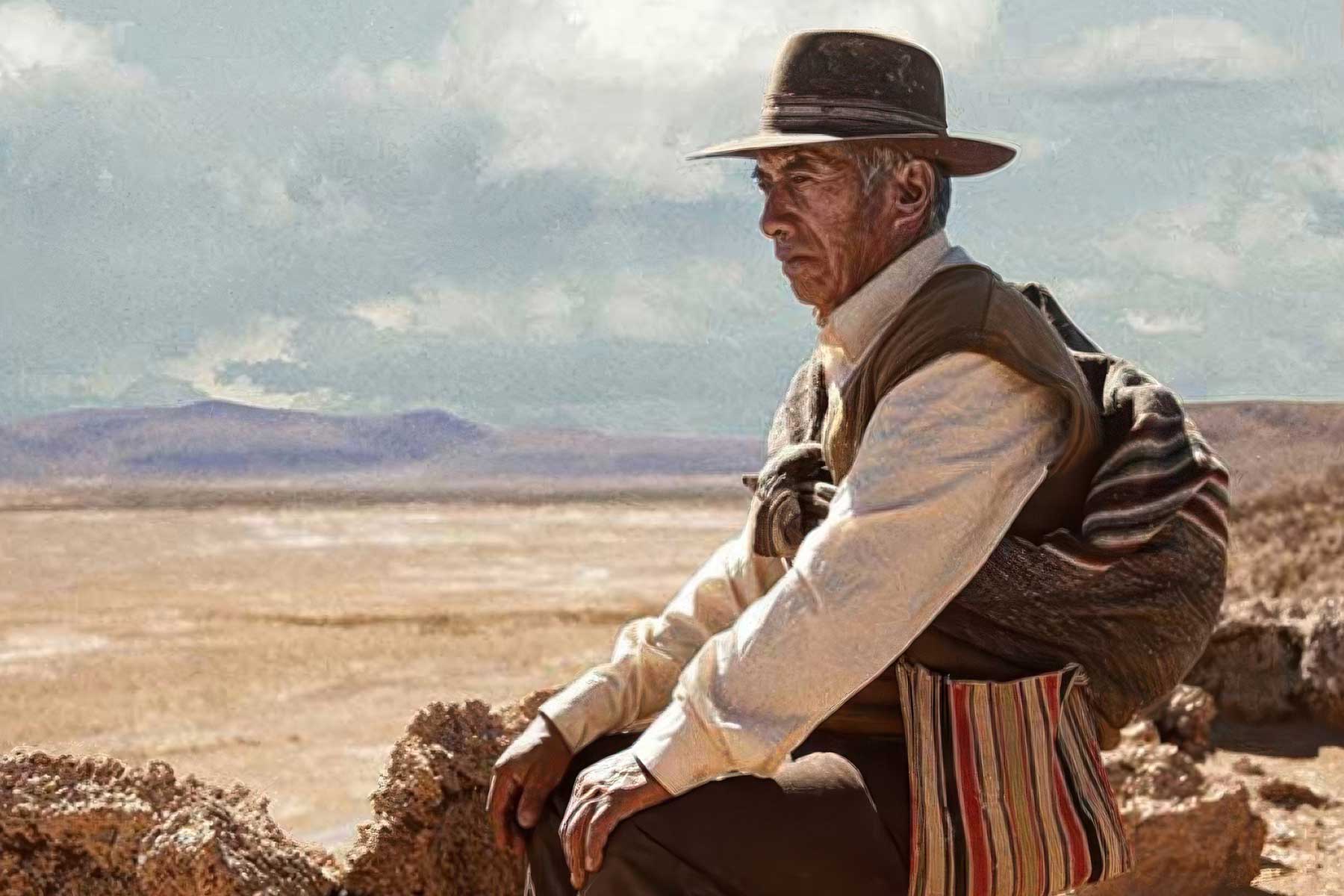

That is if you discount a film from Bolivia, Utama, Our Home, in the World Competition, a stunning, Bela Tarr like, spare but elegant mud hut take on an elderly couple living in the Bolivian high desert, almost out of water, resisting their grandson and the surety of the city, tending their llamas that crisscross the pale plains– delicate creatures with ears tied shut with red tassels to keep out the dust. Klondike and Utama are what make the long trek at this year’s Sundance from the bedroom to the living room worth it.