The western is the most muscular and malleable of all genres and, as such, it has attracted great directors over the years. Some, like John Ford, Anthony Mann and Budd Boetticher are so linked to the western that it comes as a surprise to see movies with these names attached that have nothing to do with horse, a gun, and a flower-faced girl.

Conversely, there are great directors we would never associate with the western who made some very good ones indeed. At the top of my list is William Wyler.

Long considered a master of literary human dramas like Dodworth, Wuthering Heights, The Little Foxes, Best Years of Our Lives and The Heiress, Wyler began his Hollywood career directing what were then called “oaters”; low-budget westerns meant for nothing more than a pleasant waste of a Saturday afternoon. After he hit it big, he returned to the genre twice. The first was a small one called The Westerner with Gary Cooper in 1940. His next and last wouldn’t come until 1958 and for this one he went decidedly big.

The Big Country more than lives up to its name. In fact, it is probably safe to say that this is the film that expanded the scale of the western, exercising the widescreen potential and the stereophonic sound that placed spectacle at the forefront. Even a cursory examination of post-Big Country westerns from The Magnificent Seven to Dances with Wolves will reveal deep ties to this predecessor.

And therein lies a beautiful irony.

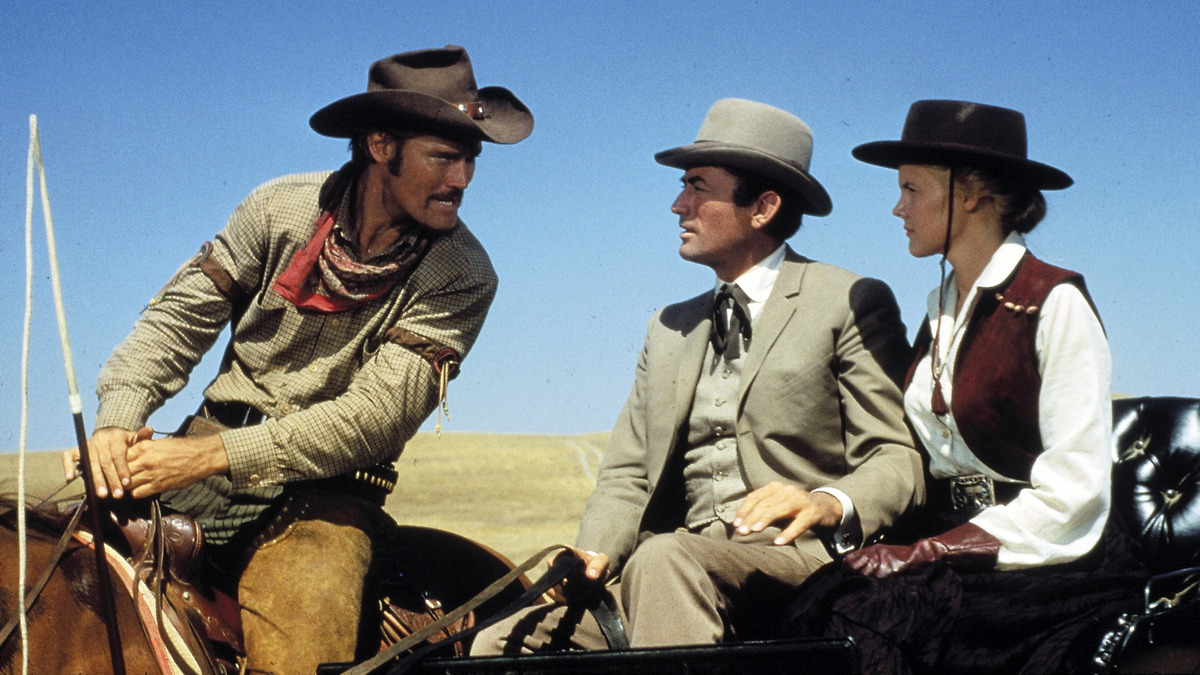

The Big Country is in many ways an anti-western. Like most westerns, it’s a story about manhood. This one, though, sets out to disprove the idea that violence is somehow necessary to establish this. One example: for two-thirds of the movie we are built up to the big manhood-proving fistfight between dude Gregory Peck and macho cowhand Charlton Heston. Such a brawl is one of the standard pleasures of a western – all flying fists and close-ups. Wyler removes even our vicarious pleasure in the violence by the way he stages it. Just as it is about to start, he cuts to a shot looking down on the two men from a couple hundred feet away and stays there. It is as though we are looking at two ants fighting over a morsel of food.

“Big” is the operative term with this movie. The score by Jerome Moross is so big that it nearly overpowers the opening image of a stagecoach thundering across the plains. Before this movie, westerns favored lighter countrified instrumentation. Here, it is as though the New York Philharmonic decided to convert Monument Valley into a rehearsal hall. Such instrumentation would become de rigeur for the westerns by composers like Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Fielding and John Barry, but it started here.

Wyler takes this bigness as the key to telling the story in a way that goes beyond the size of the frame or the loudness of the score. The performances have the same kind of epic scope, each actor doing their best to not just fill the frame but to fill the vast landscapes in which they live. Burl Ives, all intense and self-righteous fire, picked up a supporting Oscar, but the contributions of Peck, Jean Simmons, Charles Bickford, Carol Baker and Chuck Connors all match his scale. Special mention must go to Charlton Heston. He and Wyler would both go on to win Oscars in the following year for Ben-Hur, but the Heston on display here is a world away from that slice of biblical ham. His Steve Leech displays all the regular toughness we expect, but Heston finds the fears and insecurities lurking beneath the surface. The frequent bubbling up of his contradictions undercuts the well-worn aspects of the plot and keeps the tension going until the final scene.

The Big Country is itself a tangle of contradictions. For all its size, the characters are always front and center – even when we view them from a great distance. And while there is nothing original in this story about a land dispute between a cattle baron and a farmer, Wyler is constantly finding small scale human moments and observations that make it feel fresh and exciting. The result is supremely satisfying.

And that’s BIG.