George Lucas once said that it was easy to get an audience to cry. All you had to do was put a kitten onscreen then have the bad guy strangle it. What one cannot come up with, though, is an equally surefire way to get a laugh.

As any writer, actor or director will tell you, comedy is brutally hard. We all have different tolerances for humor: when and where we find it appropriate, what we find funny, where we draw the line between “laughing with” and “laughing at.” Adding to the problems for a filmmaker, comedies are created for an audience yet they are shot in the lifeless environment of a soundstage. You hope and pray that something is funny but, in truth, you simply never know until it is too late: when it is up there on that screen and playing to that audience.

Obviously, the history of cinema is a history of great comic performers and filmmakers who understood how to do this terrifying job. Directors like Leo McCarey, Frank Capra and Howard Hawks were master technicians of onscreen comedy, and no one can realistically knock the Marx Brothers, Laurel and Hardy, Buster Keaton or Charlie Chaplin. We can all recognize their genius.

Then there is Danny Kaye. I must admit that his charms frequently escaped me. I tended to find him more eager to please than is good for comedy. While I could admire his enormous technical skill, the results always tended to feel to me like I was watching a perpetual motion machine; plenty of movement, but not very moving.

Then I saw The Court Jester.

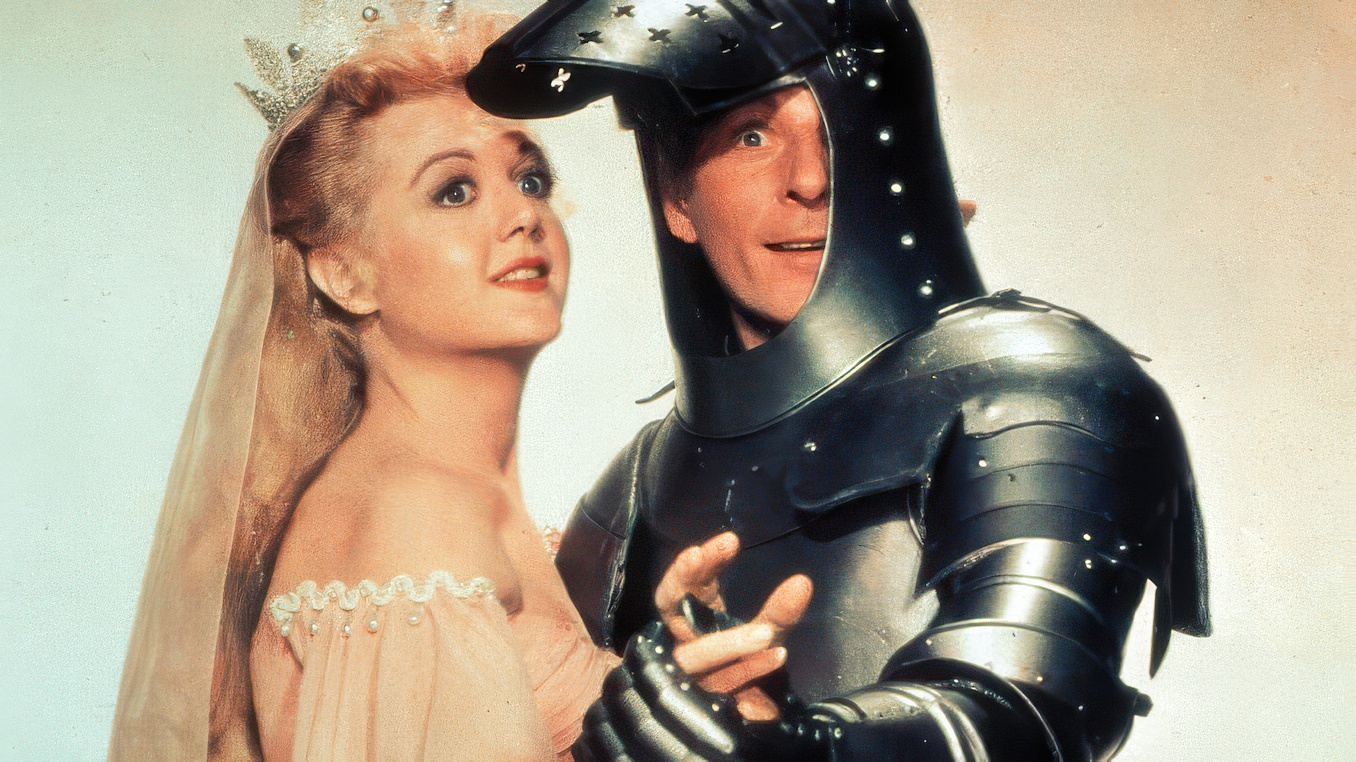

The Court Jester is Kaye’s Modern Times, his Duck Soup. This is the movie where everything comes together and Kaye delivers one of the great comic performances in a movie that remains to this day one of the funniest laugh-out-loud comedies ever made.

The plot to The Court Jester is as complicated as it is silly. Hawkins (Kaye), the jester for a group of rebels, finds that he must pretend to be Giacomo, a great Italian comic imported to entertain the dotty king (Cecil Parker) and his evil enforcer (Basil Rathbone, of course). Once in the castle, Hawkins falls under the spell of a sorceress who hypnotizes him into a new identity, one that changes with the snap of a finger. Each snap, of course, comes at precisely the wrong moment creating a seemingly endless cascade of unforeseen problems.

In truth, the complicated plot is only there to create maximum opportunities for comic set pieces. There are numerous songs and dances, including one of Kaye’s popular “git-gat-gittle” ditties where he gets to sing faster and faster while perfectly enunciating the nonsense lyrics. The real joy in the choreography, though, is in the way in which it infiltrates the staging. This is particularly true when Kaye has to make love to a princess (Angela Lansbury) while random finger snaps constantly turn him from smooth lover to terrified jester and back again, all while leaping about the bed chamber. In another literally breathtaking sequence, a knighthood ritual is radically and hilariously sped up so the king and his henchmen can get to the slaughter of Hwkins before a storm blows in.

The centerpiece joust – meant to be the death of Hawkins – is confounded when a lightning strike turns his suit of armor into a magnet attracting every piece of metal in the stadium. And it is also in this sequence that Kaye famously confuses the instructions that will keep him from accidentally swallowing a mug of poison: “The pellet with the poison’s in the vessel with the pestle. The chalice from the palace has the brew that is true.”

Part of the reason that I had never connected with Kaye before this is because he worked with many directors who were either not comedically skilled, or were simple craftsman at best. Here, Kaye is served by the writer/director team of Norman Panama and Melvin Frank. The three had worked together on one of Kaye’s better vehicles, Knock on Wood, as well as Panama and Frank writing White Christmas. The result is that each knew the gifts of the other and how best to exploit them. Also thrown into this mix was the author of “The Maladjusted Jester,” the short story on which the movie is based. It was Sylvia Fine, Kaye’s wife and songwriter.

The result of this collaboration is crazy comedy craftsmanship at its finest. What this means is that all of the seeming lunacy onscreen is the result of a very tight control. Precision guides the laughs. Throughout the film, the breathing spaces between the situations allow us to constantly catch our breath before we get to feel the joy of having it once again taken away from us. The snapping sequence and the magnetic suit of armor, for example, are funny because of the exactitude of the timing. It’s pure visual music. And just when we think the humor has hit its high point, something happens to top it one more time, then something else tops it again.

I’ve lately been watching a lot of Will Ferrell movies. I admit that I’m something of a sucker for him and his best movies will always make me laugh (Talladega Nights: The Legend of Ricky Bobby, Anchorman, Elf, etc). But seeing The Court Jester again made me recognize a fundamental difference in their approach to comedy, one that helps me to see the difference between great classic comedies and the ones we get today. The classics work hard for their laughs while the newer comedies try hard for theirs.

The difference is fundamental. The precision that has gone into The Court Jester will make you laugh over and over again because the freshness doesn’t rely on the punchline, it relies on the carefully crafted set-up. The modern comedies are punchline-driven. The lack of careful set-ups means that they have to keep throwing jokes at us to fill the screen time. It’s eventually too much. We don’t get to go with the flow so much as surrender to the onslaught.

The Court Jester is that rarest of gifts, a comedy that you can put on when you are home alone and still laugh out loud. And it accomplishes this without strangling a single kitten.